18 Oct VĪRABHADRA, THE DIVINE WARRIOR

by Marilia Albanese and Renzo Freschi

A story of love and death

Satī was a stunning beauty, it could not be otherwise since she was Devi, the Great Goddess who, through the cosmic eons, appeared in various divine families under different forms and names, only to become again and again the bride of the Great God Śiva, her companion since the beginning of time. This time around the Goddess had been born from Dakṣa, the great priest of the gods, guardian of the values of the Brahmin caste he belonged to. Even as a child Satī had manifested deep devotion to the god Śiva, which over time had turned into passionate love. She was determined to have him as bridegroom, and everyone knows that when a woman, albeit divine, ardently desires a man, she will have him, no matter if he is a god. For the daughter he dearly loved Dakṣa had convened a gathering of celestial suitors among which the young girl would choose her husband by putting a garland around his neck. But the Goddess’s beloved was not among the guests because Dakṣa had not invited him, so Satī, turning a passionate thought to Śiva, threw the garland in the air and there and then the god appeared wearing it. Dakṣa was forced to accept the fait accompli and the newlyweds left for the Himalayan solitudes.

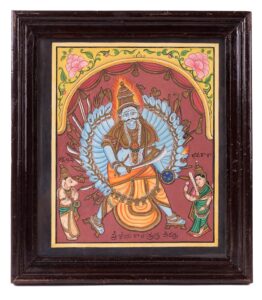

1. Karnataka or Tamil Nadu. Vijayanagar Period, 17th century. Bronze, cast by a lost wax process. 28 cm

But there was bound to be bad blood between father-in-law and son-in-law: Dakṣa incarnated the traditional order and represented knowledge based on texts and traditions. Śiva was the god of pulsions, of extreme practices, of subversion and transgression. It was just a question of time before the storm burst. It was sparked by a great ceremonial gathering, where all gods bowed obsequiously to Dakṣa; all bar Śiva, who thus roused his father-in-law’s anger: “I won’t tolerate that such a being, an outcaste, can receive a share of sacrificial offerings. Let this heretic go away and be cursed”. Untouched by the invectives of Dakṣa—who had a limited mind, as remarked in the texts—Śiva went back to his mountains. Again Dakṣa convened a great ceremony and invited all the gods except for the despised Śiva, for whom he reasserted that there would be no share of offerings. Anyway Satī decided to go to the yajña, but she was not welcomed by her father who again started to insult her husband. The Goddess uttered harsh words against Dakṣa’s obtuseness, incapable of grasping the supreme greatness of Śiva. Unable to turn her anger against her father, she let her anger consume her and burn her body. Satī, as a manifestation of the Great Goddess, was her supreme power, her Śakti, and she was versed in yogic arts, able to dominate the inner fire and to decide when to die or, better, to return into the Immanifest. Satī’s sacrifice inspired the terribile rite which took its name from the Goddess and was officially celebrated until the 19th century: in this the widow, especially if belonging to a warrior caste, sacrificed herself on the husband’s funeral pyre, thus becoming a satī. On perceiving Satī’s death, Śiva was inflamed with a deadly rage and, plucking a lock of his hair he threw it to the ground, giving life to two terrible beings: Vīrabhadra (photo 1) and Mahākālī.

The former towered to the sky, black as the monsoon clouds, with three flaming eyes, matted billowing hair and wearing a garland of skulls. The latter, a form of Kālī, a dark aspect of the Great Goddess and also Śiva’s consort, equally known as Bhadrākālī, roared angrily gnashing her fangs, adorned with snakes and severed heads. Śiva enjoined Vīrabhadra to devastate Dakṣa’s sacrifice and the latter executed the order with great ferocity together with Bhadrākālī, smashing ritual objects, contaminating offerings, killing and disfiguring priests and gods, and finally beheading Dakṣa, whose head was kicked around by Bhadrākālī . The terror-stricken divinities prostrated themselves at Śiva’s feet, chanting hymns of worship and stating that thenceforth the god would always get his share of offerings in sacrifices. The god thus appeased, they implored him to heal the wounds Vīrabhadra had inflicted on them and to bring Dakṣa back to life. Śiva granted their requests and resuscitated the father-in-law by putting the head of the sacrificial ram on his shoulders, hence Dakṣa’s second name: «ram face». It is with this likeness that Dakṣa is normally depicted (2).

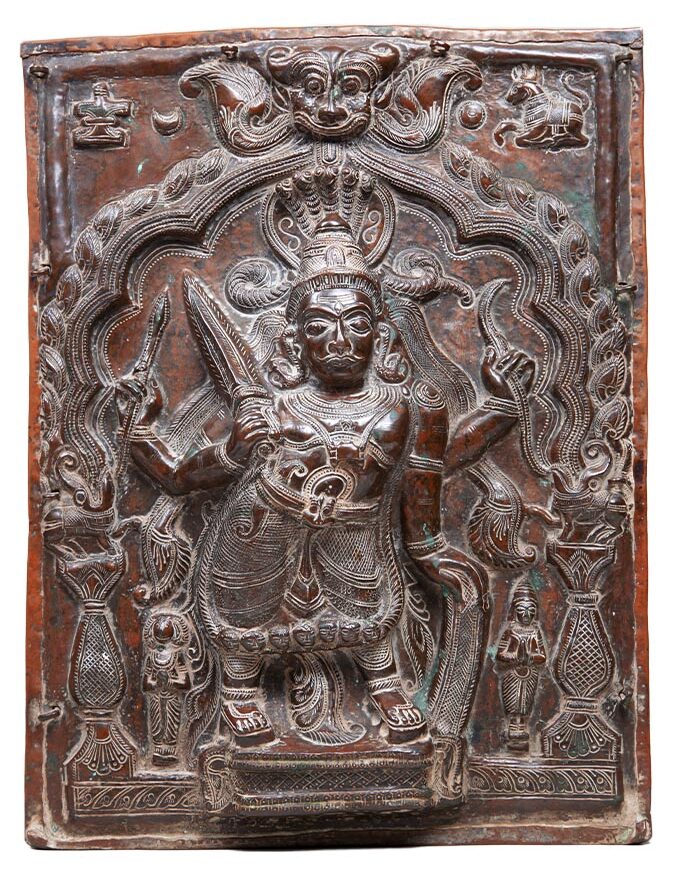

2. Plaque with especially ornate figures. Karnataka or Tamil Nadu. 17th/18th century, copper alloy, cm 26 x 18

A little-known but quite widespread cult

Vīrabhadra occupies a remarkable position in Indian popular devotion and is represented in various styles and sizes, ranging from colossal statues down to little gold jewels. Whether they be the expression of popular art, the work of excellent silversmiths, of master melters or even of tribal artisans, Vīrabhadra images testify to the wide diffusion of his cult in the different strata of people. But when did this image spread out, what materials and techniques were involved, what iconographic variants, and in which geographic areas? Because of the paucity of studies about this warrior, the picture is rather confused, but some elements are nevertheless clear. The spread of Vīrabhadra’s cult mainly concerned the area of the Vijayanagara empire, to wit the Deccan plateau (the present-day states of Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka) and parts of current Tamil Nadu, Orissa and Kerala. His cult soon became popular, mainly due to historical and religious reasons. In fact, in this projection of Śiva as a fierce warrior the belligerent Vijayanagara empire saw not just a symbol of military qualities, but also a guardian of Hindu traditions threatened by the inroads of the Islamic Sultans. It is not for nothing that vīrabhadra, meaning “celebrated hero”, was recognized as the tutelary deity of warriors. At Vijayanagara (present-day Hampi), capital of the kingdom, a temple was dedicated to him in 1645, the Uddāna Vīrabhadra, where an almost 5 mt tall statue of the god is probably the largest in the whole of India. It was in fact his heroic dimension that helped his penetration into tribal areas too, where the cult of village protectors was widespread. In the turbulent history of central-southern India Vīrabhadra’s popularity remained extremely high even in the 19th century, when he lost his symbolic function of religious bulwark to probably acquire the decidedly more political one of opposer against British occupation. In the heyday of the warrior-god cult, between the 16th and 19th century, production of images was massive, as also shown by the Berger collection, comprised of some hundred items. Some were destined for important or minor temples, others were placed on home altars, others still were bought or commissioned as ex-votos, testifying to a deep devotion. In this case, the larger the faithful’s financial resources, the more precious the metal employed would be, like silver and 22-carat gold (5 and 12).

In large shrines just as in more modest temples Vīrabhadra dominates on wooden panels of the colossal processional chariots and on banners hanging on temple walls, but it is above all on altars, as true effigies of the god, in home shrines and also on personal objects that the divine warrior mostly appears. Some have a handle on the back (7 and 8) which allowed the temple Brahmin to hold them during ceremonies, making them turn clockwise and bringing them near the devotees so that they could touch them as if to absorb the god’s radiating power through physical contact. Many plaques are worn down by centuries of ritual manipulation, for the images of the gods (mūrti) are daily washed, sprinkled with special substances, dressed or covered in flowers. In some of them even the relief has disappeared, barely leaving the figures’ profile (12 and 18).

Thanks to a network of artisan corporations, preservers and users of techniques and iconographies passed on from father to son, Vīrabhadra is sculpted in stone and wood, molten in bronze statues, hammered in repoussé on copper, brass, silver and gold sheet, carved on amulets to be worn around the neck (9), depicted on weapon hilts (10). A protective presence which gives strength and courage to those who worship him.

9. Pendant, Karnataka, 19th/20th century, repoussé gold and glass paste, 5,5 x 3 cm

10. Dagger, South India. 17th/ 18th century. Bronze and iron.21,8 cm.

Stone is the least used material: the earliest and rare statues of Vīrabhadra, usually with four arms, appear in the 9th/10th century in niches in the outer walls of temples housing the divinities related to the main idol in the cella (11 and 21). The most common support for Vīrabhadra images are metal plaques made by the lost-wax process or embossed.

Although manufacture of metal plaques likely started before the 15th century, its highest popularity was reached between the 17th and 19th centuries, chiefly in southern India and notably in the current states of Karnataka and Maharashtra. Unfortunately the lack of specialist studies makes it difficult to assign these plaques to a geographic area with a precise date; the regional issue remains problematic. From a formal viewpoint these plaques can be divided into three different, non-comparable styles. The first one—which we could call classical or noble—follows the stylistic features of the artistic tradition connected with the large Hindu sacred complexes and defines all details with great precision and elegance (2). The figures are well-proportioned, graceful, often in the stance called tribhaṅga or “the triple bend” which accentuates the sense of movement (1 and 20). The second style interprets the first one with forms in which the power of the icon prevails over the harmony of figures. The bodies are stiffer and less detailed, even if some details convey the creative inspiration of the craftsmen who made them. These are plaques made in provincial workshops, not in the exclusive ateliers linked to the most important temples (22). The third category is that of the ethnic groups still living in vast areas of India, tribal groups which, while converted to Hinduism, still cling to autochthonous cults and traditions. Stylistically these plaques are totally different from those just described: the figure of the god is not merely stylized, but changed into a “primitive” image where realism and proportions do not follow the canons of classical Indian sculpture (15). Formally they have a traditional structure, but it is elaborated with great creativity. Regardless of style, iconography does not undergo great alterations over the centuries, for sticking to the rules set by tradition guarantees sacrality of the image and its thaumaturgic power.

14. Maharashtra or Karnataka. 17th century. Copper alloy. 35 x 15 cm. (above)

15. Maharashtra. 19th century. Bronze. 25 x 17,2 cm .( below)

A thousand details

Metal plaques are usually rectangular in shape or ending in a cone or triangle. The upper portion often carries a flame motif. Vīrabhadra is in fact described as appearing in a flickering of fire. The more elaborate plaques show the god under an arched structure supported by more or less ornate pillars or columns called prabhāvali, symbolizing the halo of light, prabhā, associated with a divine being. The arch is often topped by flaming tongues and the capitals may feature mythical animals like the makaras (water monsters) and the yali, a sort of leogryph (16). At the cusp of the arch is a lion mask known as kīrtimukha or “glory face”, whose origin is associated with a myth where, infuriated by the arrogance of a demon, Śiva had opened his third fiery eye and had generated a frightening ravenous monster. There being nothing to satisfy his hunger, the demon was instigated by Śiva to devour himself. When nothing was left but the monster’s face, the god stopped him proclaiming his courage and fidelity and commanding that his image should be carved on Śaivite temples as kīrtimukha or “glory face”. The motif of the feral mask became a distinctive decorative element of the religious architecture and art in the whole of India.

16. Karnataka. 19th century. Bronze. 29 x 25 cm

17. Tamil Nadu. 19th century, repoussé silver, 21,5 x 14 cm

In the top corners of the plaque the Sun and Half Moon can be seen, their position being interchangeable. The two heavenly bodies are generally represented as a circle and a half-circle, but there are instances in which the sun is rayed or in the shape of a flower. Next to the Sun and Crescent we see the liṅgayoni—the symbol of the union of male and female—and the bull Nandin which is Śiva’s mount. Vīrabhadra’s posture may vary: When standing, he can be either in full frontal stance or slightly resting on the right-hand leg, both feet pointing forward, set apart at a variable distance, the left foot sometimes turned outwards (more rarely in the opposite configuration). When moving, the hips rotate chiefly to the left, with feet pointing in the same direction, while the upper trunk remains frontal (14).

18. Maharashtra (?). 19th century or before. Bronze.

20,5 x 16,5 cm

Vīrabhadra’s head is often topped by a cobra, shown with an open hood or polycephalous—the heads always being in odd numbers, five or seven. The god wears a peculiar headgear, a tiara in the shape of a bamboo basket which in some cases is extended by winglets behind the ears underlining its function of helmet. Vīrabhadra’s face may feature some elements relating him to Śiva: the third eye on the forehead and above it the three horizontal lines which denote Śaiva adepts. Further distinctive elements are the moustache (3), beard and the cleft chin. The garment consists of a sweep of cloth worn in various fashions around the hips and held at the waist by a belt with a buckle, often in the shape of a lion head. Vīrabhadra wears wooden sandals consisting of a sole with two high heels, at the front and rear, and of a small stick with a tiny pommel which fits between the big toe and the second toe (7). The god is rarely shown barefoot and always wears ankle supports. When two-armed, the god wields a sword in the right hand and a shield in the left (19). When four-armed, the upper hands usually hold bow and arrow or a quiver. At his most powerful, the god has ten or more arms, with hands holding as many ritual objects.

Vīrabhadra wears a profusion of armlets, bracelets, necklaces consisting of one or more strands of pearls, tight chokers, or with amulet boxes. Typical is the necklace of rudrākṣa, “Śiva’s eyes”, faceted seeds of Elaeocarpus, a plant sacred to the god. From the left shoulder the cord of the initiation ceremony falls on the right side. It is a must for males of the first three Hindu castes when they are placed in the care of a teacher. Always present is the garland of skulls indicating the frightening and baneful aspect of Vīrabhadra. Beside Vīrabhadra’s feet are Dakṣa, with his ram head carrying powerful curved horns, usually placed to the god’s right, and Bhadrākālī to his left. Dakṣa’s iconography is almost invariably the same: standing with joined hands in deference. Depictions of the Goddess on the other hand can vary, warranting the supposition that the serene and composed traits are a hint at Satī and the more wrathful traits represent instead the rage of Śiva’s bride turned into Bhadrākālī, with tiara and helmet, sword and shield. In plaque 19, for instance, the goddess wears the typical sari of Indian women, whilst in 2 she is in combat attire. Variations in the dress characteristics are most likely due to the fact that female dress changed according to the period and the different geographic areas.

Among the vast quantity of hand-crafted plaques those made by a true artist are easily identified because of the energy emanating from the god’s body and his evident frenzy. These powerful, compelling works are not just to be found in the plaques we called noble, but also in the tribal production where, despite a lower level of detail and simpler forms, the expressions of some Vīrabhadra faces are reminiscent of ritual masks or forest spirits.

When in the mid-1970s I began to take an interest in Indian folk bronzes like the Virabhadra plaques, I used to buy them in New Delhi from small junk dealers who often sold them by weight. At that time in India (as in Italy too) scrap-metal dealers were still a common sight on the streets, buying metal objects no longer in use because they were broken or worn out. Some of these objects were selected to be sold individually, others would be sold by weight, and the remainder would be sent to the foundry to be melted and reused for new items. One might object that statues of divinities are sacred and therefore should not be sold or destroyed, but in the Indian religious tradition the murti (divine images) are not intended as representations of the divine, but as the gods themselves, who therefore must be absolutely immaculate: any blemishes, broken or worn parts are not acceptable, and in those cases the statue must be replaced. Hence it was inevitable that these plaques, often worn out, would be given to the scrap-dealer for recasting, and that is why many of these works were actually saved from being turned into metal bars.

Another reason why many images of Virabhadra were sold by the temples and by the faithfuls who owned them is the fact that in India the gods too are subject to the vagaries of history which increase or decrease their popularity. The most significant example is that of Brahma, one of the oldest deities, to whom very few temples are dedicated across the whole country. The cult of Virabhadra too -very popular until the early 20th century, for it was the emblem of the warrior defending religion from enemies and invaders- declined in popularity, a fact which led to many panels and statues being sold.

The most important collection of Vīrabhadra images in the world is the Milanese one of Paola and Giuseppe Berger, numbering many thousand pieces datable between the 13th and 20th century. Here the various inflections of the Vīrabhadra image are illustrated: as a statue for display in temples, hence of considerable size, of granite and wood; as an image painted on paper, cloth, wood, glass, for the home cult as an idol placed on special altars or as a repoussé figure on plaques of various metals; and further, chiseled on sword and dagger hilts, jewels, pendants and amulets. –> 21 October – 19 November 2022

(Excerpt from the article published on Arts of Asia, Autumn 2022, thanks to the Editor’s copyright policy)

Photo: Pietro Notarianni

No Comments