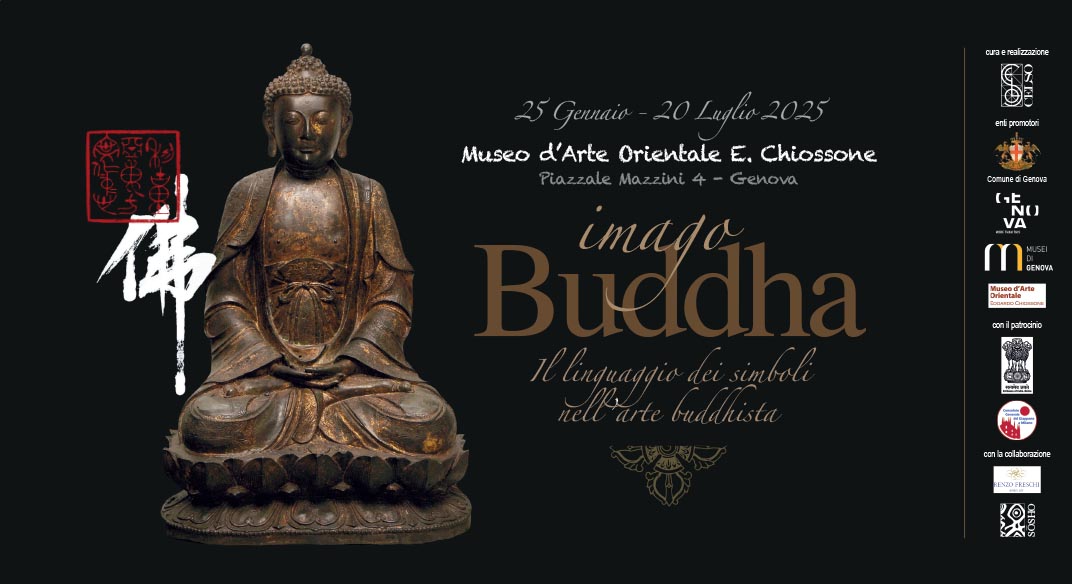

11 Feb IMAGO BUDDHA The language of symbols in Buddhist art

Not many people know that the first museum entirely devoted to Far Eastern art in Italy was the Chiossone Museum in Genoa, which opened in 1905 thanks to Edoardo Chiossone’s generous donation of his collection of Japanese art to the City of Genoa. Chiossone had lived for a long time in Japan, where he had worked for the state mint and designed the first Japanese banknotes; when he died in 1899, the tens of thousands of works of art he had collected came to Genoa and were placed in the first location, which then remained closed for many years.

Finally, in 1971, the museum was moved to its present location, the Villetta di Negro on top of a small hill surrounded by a beautiful garden. After another temporary closure for technical adjustments, the Museum finally resumed regular exhibition activities under the direction of Dr. Aurora Canepari, to which was added the programming of important scientific and artistic exhibitions. “Imago Buddha, the Language of Symbols in Buddhist Art” can be considered the first in a series of events intended to restore the Museum to the prestige it deserves, given that it is considered one of the most important museums of Japanese art in all of Europe.

The exhibition opens in the beautiful hall on the ground floor, where some of the most important bronze sculptures from the Chiossone collection are presented. The purpose of the exhibition is to make understandable the symbolism of Buddhist images and the meaning of the many gestures and postures. All works are accompanied by cards that reveal their meaning and ability to evoke a spirituality that aims to pacify the soul and mind. In addition to having an educational and informative intent, the exhibition also enhances the aesthetic quality of the sculptures, which placed in this large space allow visitors to appreciate the serenity of their faces and the elegance of their bearing.

The Buddha with two bodhisattvas.

Gandhara art.

1st-3rd century, schist.

They are statues that belong mainly to Japanese and Chinese art, to which three magnificent Thai works and three stone sculptures from ancient Gandhara have been added. In this region, between present-day Afghanistan and Pakistan, Buddhist art took on the Hellenistic guise introduced by Alexander the Great around the 3rd century BC. It was precisely the elegant Greek-style drapery of the Buddha’s robe that in the first centuries of our era became the pattern that spread throughout Asia and is thus also found in Chinese and Japanese statues of the Enlightened One.

The works presented were chosen from Chiossone’s impressive holdings, some exhibited for the first time: magnificent works for their refined elegance and profound spirituality. Prominent among the more than one hundred is a beautiful Chinese Sakyamuni Buddha of the 14th/15th centuries in lacquered and gilded wood, seated in the classical “lotus” position, raising his right hand in the gesture of “teaching,” that is, of transmitting the Doctrine to the believer in order to attain Enlightenment.

Standing out in the center of the hall is the large upright 17th-century bronze statue of Juichimen Kannon, a Japanese manifestation of the Indian bodhisattva of Compassion Avalokitesvara, with his head crowned by 10 other heads and with that of Buddha Amitabha at the top.

But one of the most fascinating masterpieces in the entire exhibition is certainly the “Amitabha Triptych” consisting of the Buddha in the center and two bodhisattvas on either side, in 18th-century gilded wood. In addition to the intense hieraticism of the Enlightened One, the unusual position of the side figures is striking: the one on the left slightly bent at the knees in a gesture of deep devotion and the other seated with head bowed in reverence. Though separate, these statues make up a single whole from which a feeling of great harmony emerges.

Amida Sanzon (Amitābha Triad)

Japan, 18th century

Carved and gilded wood

Along the entire side wall are the 25 educational panels that enable visitors to understand the philosophy, symbolism, and iconography of Buddhism.

Fudō Myōō

Japan, Middle Edo Period (1673-1750), Kimura Shōgen Munenari, 17th-18th centuries

Bronze casting with traces of gilding

Dainichi Nyorai

Japan, middle Edo period (1673-1750), dated 1673

Bronze casting

Jūichimen Kannon

Japan, early-middle EDO period (1600-1750), 17th century

Bronze casting

The exhibition was designed and produced by CELSO, the Institute of Oriental Studies in Genoa, for 30 years one of the most active institutions in the teaching of Asian languages and cultures in Italy. The program of lectures and study organized by Alberto de Simone and Emanuela Patella, founders of CELSO, is a point of reference for those who love Asian Cultures, and this exhibition, of which they are also Curators, testifies to its importance.

Renzo Freschi

No Comments