14 May Ganesh Sthapana – Embroidered Talismans

(A short essay)

Between 1975 and 1985 I had a driver-friendin New Delhi with whom I would travel to Rajasthan and Gujarat in search of “treasures.”.In Saurashtra and then in mythical Kutch we would stop inalmost every village and sometimes even at encampments of Rabari nomads in order to buy their embroideries. I loved those encounters which opened the doors of a genuine India for me, that of the countryside and of traditional life, with its hardships but equally its sweetness.

Once I saw, hanging at the entrance door of a house, a square piece of embroidered cloth at the center of which was a very stylized figure, andonly its long trunk betrayed it as Ganesh, the Hindu god with an elephant head. Back in Ahmedabad, the capital of Gujarat, I called on Mannu Bhai, a merchant of traditional embroideries, a genuineexpert on regional textile art, and I listened to him spellbound when, picking up an embroidery from a pile, he told me which ethnic group and village it came from.Hethen taught me how to interpret its figures, symbols and meanings. It was he who introduced me to the world of Ganesh-Sthapanas.

I found it amazing at the time – and still do to this day – that each of those embroideries was different from one to the next, and I was deeply fascinated by the synthesis and stylization verging on the abstract with which the elephant-god was depicted.

Most Ganesh-Sthapanas come from Saurashtra, an agricultural and textile manufacturing province of Gujarat in west-central India, and are pentagonal in shape (a triangle placed above a square), thus looking like a stylized temple. They are made of cotton cloth strengthened on the back by a lining lending them sufficient rigidity so that they can be hung. The drawing is outlined in black ink and the various parts are embroidered, using various types of stitch, with silk or cotton threads. Several small round mirrors are often sewn onto the cloth as a symbol of the god’s lighting power, and one can imagine the compelling effect of their reflections when hit by the light of a candle or lantern in a room with no electricity. Lastly, a cotton ribbon serving as a frame is sewn on the rim and eyelets are placed at the five corners to keep it stretched when it is hung above the entrance door. The supporting cloth is usually yellow or orange, the colors of the sun and of joy, but sometimes it can be white as a symbol of purity, orrarely in other colors.

Of course the central subject of every Sthapana is Ganesh, the god who “removes all obstacles.”This definition takes us back to a time – between the second and first millennium BC – in which man needed the elephant’s strength to cut down forests, widen fields and harvest the crops, hence his worship. When the Vedic religion absorbed more archaic rites, the cult of the sacred elephant slowly seeped into Hindu iconography, but it never lost its popularity. Several myths tell us the story of his birth and the reasons for his funny look, characterized by an elephant head and a massive belly. According to the most popular of them, Ganesh, a beautiful child created by Parvati to guard her own dwelling, would not let Shiva in, the goddess’ companion. The fuming god cut off Ganesh’s head and only the intervention of Brahma, Vishnu and of the repented Shiva himself could appease the mother’s rage. Ganesh lived, but his head was replaced with that of the first animal passing by: an elephant.

All Hindu gods are associated with an animal-vehicle and Ganesh rides a mouse which “overcomes all obstacles” in order to reach food. However, this too is a metaphor, for in reality the mouse steals the farmers’ food and its presence at the god’s feet, sometimes in chains, indicates that the world of nature and that of animals are totally controlled by the gods.

The structure of Sthapanas is almost invariably the same: inside two or more floral frames delimiting the sacred space, Ganesh sits on a throne, a symbol of regality, flanked by Siddhi and Buddhi, consorts or faithful maids, depending on the various legends. Siddhi embodies wisdom and spirituality, whilst Buddhi is intellect and the success that sometimes follows. But Ganesh is never alone, and so Sthapanas reproduce and concentrate in themselves the world of the Saurashtra countryside: myriads of birds – peacocks, parrots, doves – colorful flowers and then the elephant, horse, bull, cow, mouse, plus the sun and various other symbols of Hinduism.

For centuries the dowry of young brides in the region consisted, besides the traditional jewels, of a considerable number of fine fabrics and embroidered costumes that were piled up on a wall in the house and covered with a large embroidered cloth. The Ganesh-Sthapana was the first to be made as a well-wishing and devotional gesture to the most benevolent of gods, and for this reason we can call it an “embroidered talisman.”It seems that the first Sthapanas go back to the mid-19th century and that they soon became popular in the whole region. While the composition remains the same, various local styles exist, sometimes using different techniques.

As Sardar S. Hitkari writes in his passionate and fundamental book Ganesh-Sthapana. The Folk Art of Gujarat, “any modern artist would envy these abstract nonfigurative creations by ladies who never had any formal education in art.”Up until a few decades ago, before television brought new realities into their world, these populations lived in accordance with century-old rhythms. For young girls preparing their dowry and for women in the family, embroidery was a time of relaxation from the heavy daily toil and a moment to be shared with the other women. For each future bride embroidered textiles thus became an expression of her own personality, something uniquely herswhich she would take into the husband’s house when leaving her family. Therefore Ganesh-Sthapanas also represented a hope, a sort of talisman for a hopefully happy future.

India’s recent modernization spelled the end of many traditions, particularly in the countryside, and dowry embroideries have been replaced by other more trivial and less identitifying forms of dowry. Nevertheless the religious power of Ganesh’s image remains so strong that even today Sthapanas continue to be manufactured for commercial purposes. Those published in this article and selected for the exhibition were collected in the 1970s and 1980s, many of them go back to the first half of the 20th century.

Renzo Freschi

“This article is dedicated to Sri Mannu Bhai, a master in the knowledge of the phenomenal cultural heritage represented by the art of embroidery in Gujarat”.

Renzo Freschi

52 x 54 cm

Is this Ganesh not sweet, looking like a hippo with yellow eyes and with a small mirror for belly button? And don’t Siddhi and Buddhi look like two prehistoric figurines pictured, or rather caught by a flashlight, in a dance step? And don’t the two parrots seem like a doodle? Few elements rendered with a modest technique, but the message is loud and clear like an icon.

62 x 47 cm

Some Sthapanas belong to a more “cultured” school, probably influenced by English embroidery; the style is more realistic, the composition more regular and symmetrical. The figures are well defined by a dense and compact embroidery which indicates greater technical ability than the crude manual skill of the more “popular” style. Surely there is less spontaneity and fantasy but one can appreciate the elegance of the floral weaving and the greater chromatic balance.

59 x 55 cm

Here Ganesh is all red, like his sumptuous dress; he has white beady eyes and two black mice lie at his feet. The god and his two faithful companions are placed inside three niches surmounted by a pair of bulls. In this case too, the chromatic contrast between the deep red of the figures and the yellow background brings out the large image of the god.

57 x 62 cm

This is a Ganesh-Sthapana in a “naturalistic” style, embroidered on white cloth with a cotton thread. The square shape contains the traditional, pentagonal one featuring two frames, a wider one with flowers and birds and a narrow one with small round mirrors. At the center Ganesh, with two mice at his feet, seems caught in a dance step; he is not accompanied by the usual devotees, but by a pair of cows, while the naturalistic taste of the composition is apparent in the beautiful peacocks with glimmering feathers standing by the god’s side.

55 x 48 cm

In the upper register Ganesh, Siddhi, and Buddhi are surrounded by myriads of birds and by a two-headed horse – a typical way of representing a group of animals in Indian painting. In the bottom register we see two images of Shiva wielding the trident and riding Nandi, the sacred bull, identified by the yellow horns. It is a folk banner introducing mythological elements in a domestic environment – the description of evocative symbols in an archaic and powerful form. The astonishing similarity between this Sthapana and the one shown on p. 65 of S.S. Hitkari’s book suggests that both might come from the same family group, the evidence of a tradition passing from generation to generation.

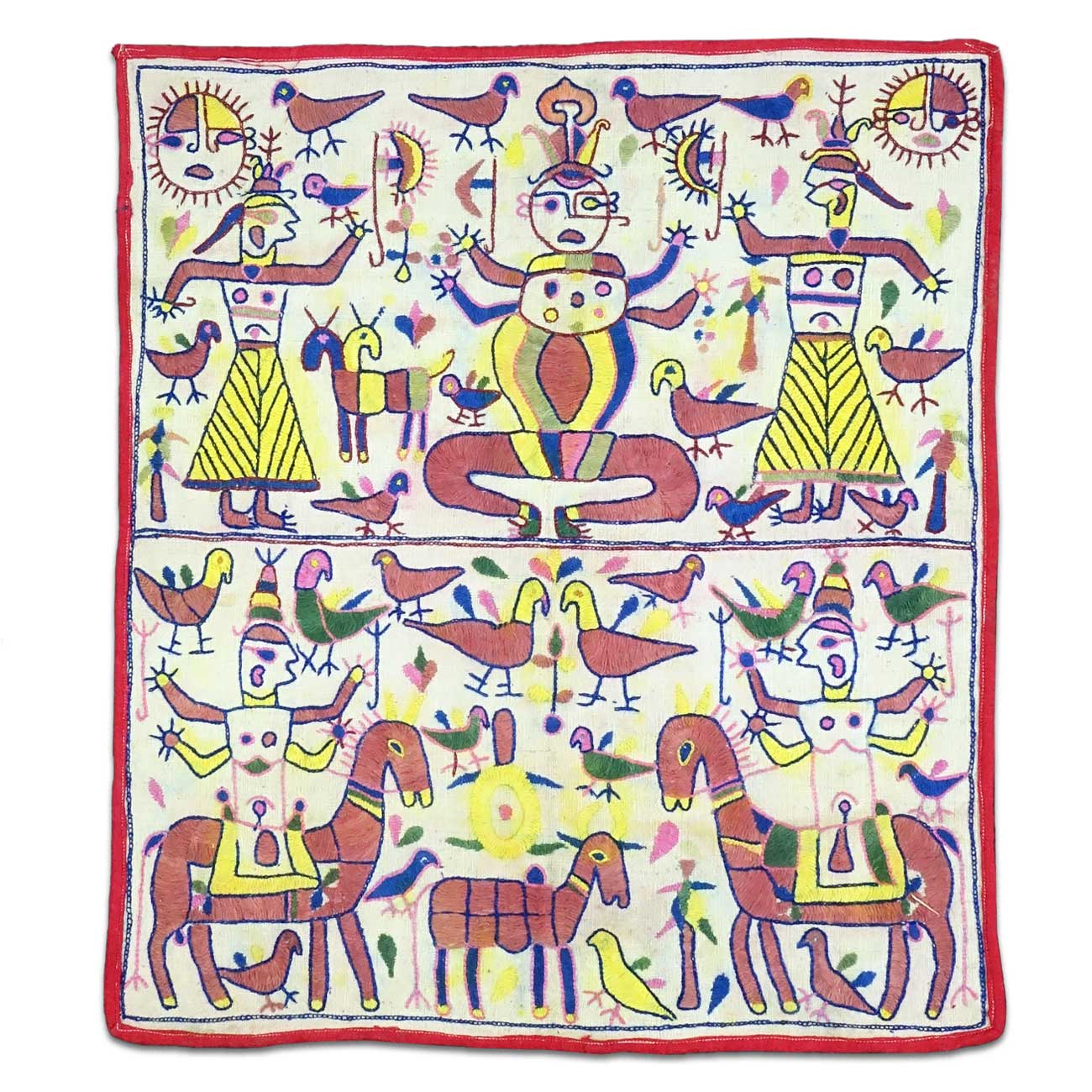

55 x 52 cm

This square Sthapana is divided into two registers. In the upper one Ganesh is flanked by Siddhi and Buddhi – his two most faithful devotees – and all three of them are completely surrounded by various multicolored birds. On top right is the sun with yellow rays and on the left the moon with pink rays, both with a moustache. The lower register is filled with small and large birds, almost a flock ready to take wing; but among the birds there are also a bull and a cow with her calf and other animals with a sort of stylized mane, probably lions.

First half of the 19th century, Surindernagar area, raw cotton embroidered with silk thread.

67 x 62 cm

This Ganesh-Sthapana is quite elaborate but equally well-ordered both in the composition and in the choice of a mix of just three colors – burgundy, light green and white, all on an orange background on which small round mirrors are applied. All subjects – Ganesh, Siddhi and Buddhi, the sacred cows (featuring a single central eye) and the parrots embroidered under the god’s arms – are rendered in a balanced and effective style. The figures are made of sections in two different colors, like pieces of a mosaic.

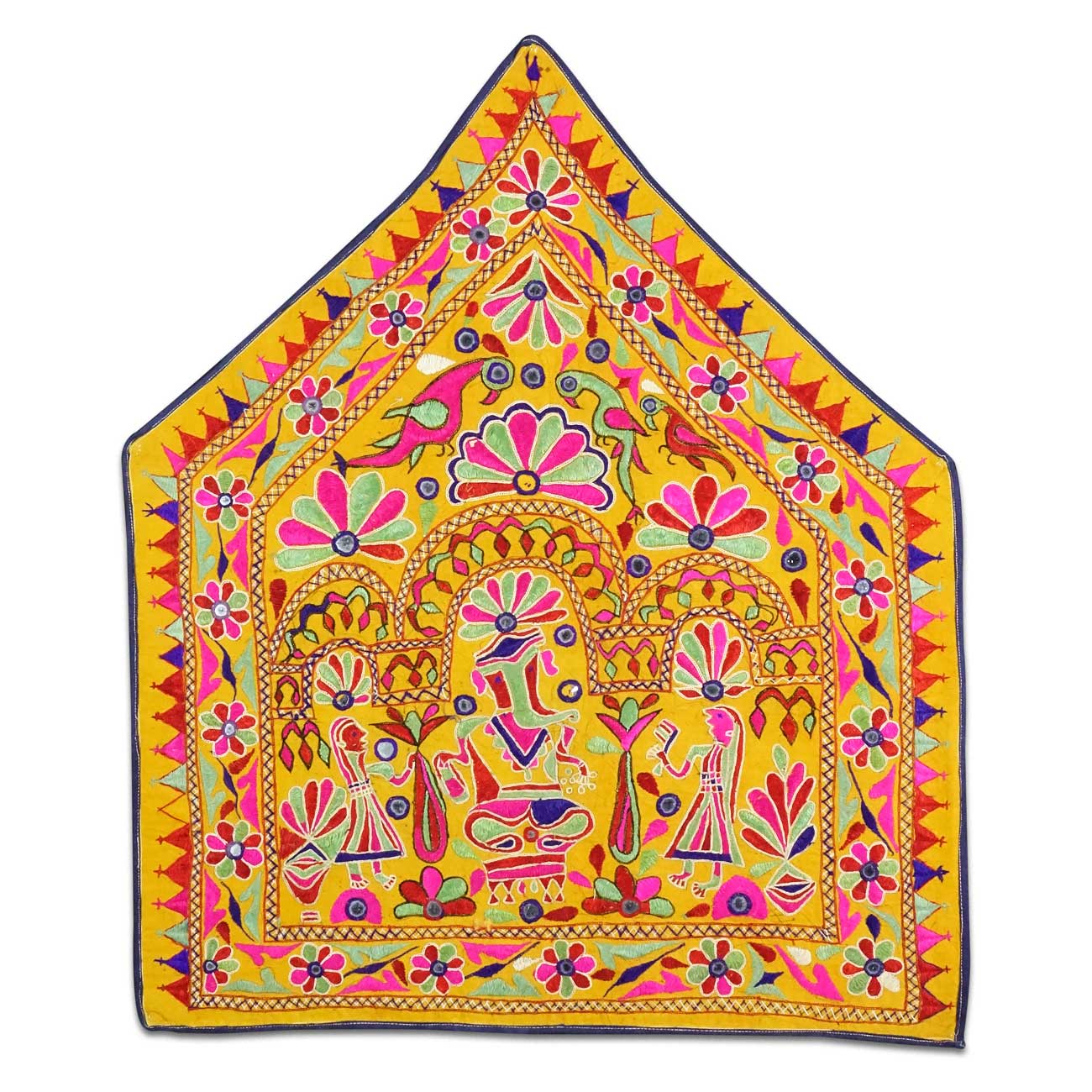

72 x 61 cm

The saffron-yellow cloth is embroidered with brightly colored silk threads. The composition is particularly refined: at the center of sumptuous floral frames Ganesh and his faithful devotees are protected by a triple, densely decorated arch supported by two columns, a realistic depiction of a temple altar. Floral offerings cover the ground. The contrast between the color of the fabric and the deep tones of the embroidery make for an almost hypnotic effect.

65 x 57 cm

This is the most animated Sthapana in the whole collection, with figures turning around the central mirror, possibly a symbol of fire or of the sacred altar. Siddhi and Buddhi are plain cylindrical forms on which the head rests like a vase. They raise an arm as if to wield the large fans beside the god’s head. At the top, four figures – with the same incredible form as the maids and Ganesh – seem to be engaged in a wild dance. In this case, too, we perceive the extraordinary imagination of some Sthapanas, but also their pictorial quality making them true works of art. I have had this painting hanging on a wall at home for over thirty years, and even now when I look at it my heart opens and I gape before this small, spontaneous masterpiece.

56 x 57 cm

Sometimes words cannot describe the inventiveness of whoever made such an embroidery which, whilst within the tradition, is different from anything else. Lots of small white dots are sprinkled on all human, animal and floral elements, covering them like snow flakes and creating a curious aesthetic effect. Within the outer rim featuring silver trimmings strange collared and chained animals appear with open jaws – are they fierce or mythological?

60 x 53 cm

This is possibly one of the most realistic Sthapanas in the whole collection. Ganesh, all in pink and wearing an elaborate conical crown, displays his bulging belly from which his four arms outstretch holding the traditional ritual implements. His trunk has just grabbed a red sweet he loves, his chest is glittering with silver sequins. Along with the small mirrors lighting the scene populated by peacocks, elephants, and mice, all in blue, they seem to represent the benevolent light emanated by the god. From the bottom register five festoons descend, like the ones decorating houses and temples during religious festivals.

68 x 58 cm

In the almost blinding multitude of flower garlands and petals filling the space, the two parrots on top and even more the figurines of Siddhi and Buddhi, with two mirrors for heads, almost disappear. Just the blue color and the extremely long trunks enable us to identify the pair of elephants at the bottom. But this confusion contains another dimension, enclosed by a silver ribbon, in which sits Ganesh, covered in mirrors and silver sequins barely hinting at his shape. This sacred space is separated from the worldly one, and only devotion allows accessing it and enjoying its reflected light – folklore is not forgetful of the divine.

56 x 55 cm

Who could recognize in these three vaguely human forms Ganesh with his Siddhi and Buddhi, were it not for the god’s trunk and crossed legs? And what do the horizontal bars above the figures mean? And why are the animals and the other figures in the outer frame immediately identifiable, as opposed to the abstract forms and various colors of the three central figures? This is the extraordinary fascination of Ganesh Sthapanas: power to the imagination!

50 x 38 cm

Sometimes the drawing becomes simple and essential, and a naive taste prevails while still preserving the charm of the best “raw art”. The two devotees Siddhi and Buddhi raise their arms as if dancing, whereas the two mirrors on their heads symbolize the water jars habitually carried by Indian women. The scene is a veritable festival of colors: each figure is embroidered in a different color and even Ganesh is half red and half burgundy. At his feet two blue mice with pink heads are secured with a chain to the alms tray.

53 x 46 cm

Here is another excellent example of the gift for succinctness that Saurashtra embroiderers reveal in their Ganesh-Sthapanas. The god is shown as two superimposed ovals in a figure of eight, with two mirror eyes allowing us to guess where the head is. Siddhi and Buddhi are formed by a rhombus and a triangle, with the crowned heads made of a series of small mirrors. The rest is embroidered with floral motifs on which the dark red shapes of the three main figures stand out.

No Comments