15 Sep THE MYSTERIOUS BEAUTY OF KONDH BRONZES

di Renzo Freschi

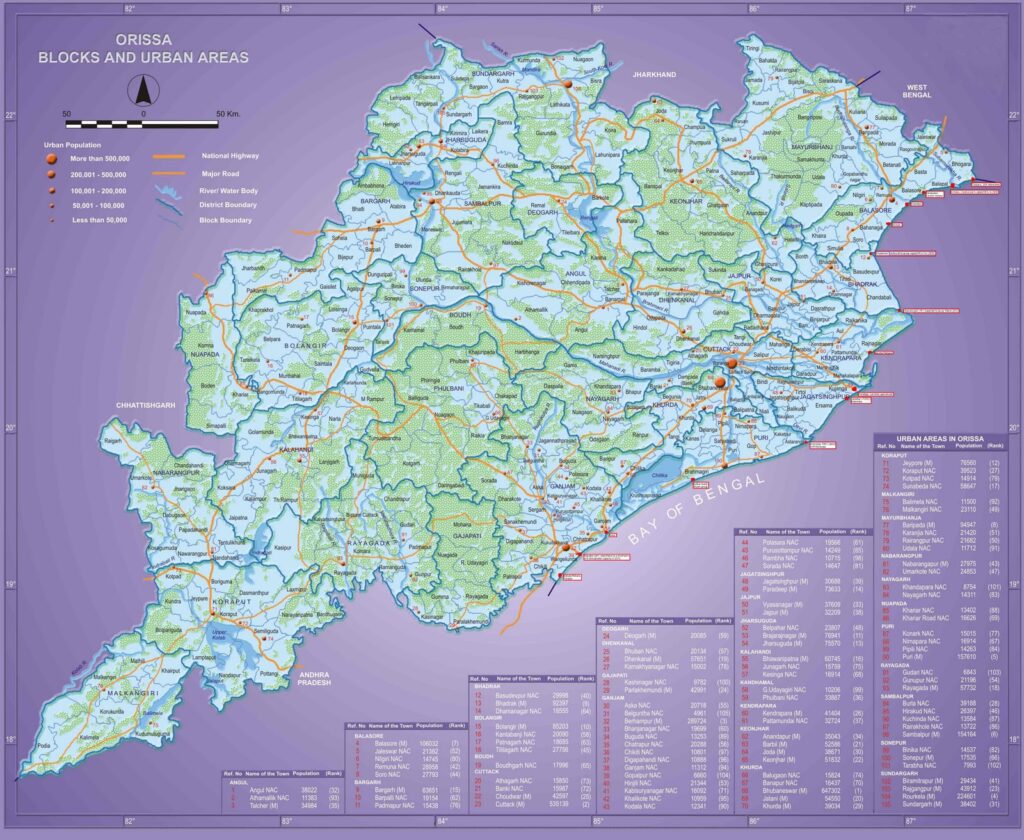

Protected for centuries by the virgin forests of Orissa (Odisha), a state of eastern-central India, the Kondh tribes were first “discovered” around 1835 by a British expedition on the track of a raja (king, prince), a tax dodger and an anti-British instigator who had found shelter and protection among the Kondh.

The problem of the rebellious raja was solved by the British with a war that lasted three years and a repression verging on genocide, then they set about tackling the most disturbing aspect of Kondh culture, human sacrifice, managing by fair means or foul to convince them to replace human victims with the sacrifice of wild oxen. Thereafter, apart from occasional studies and officer reports, the Kondh were all but forgotten until the end of the 1960s, when the arts and cultures of Indian natives (adivasi) were discovered by Indian and foreign anthropologists and scholars

Eventually the importance of an art was understood which a passionate Indian artist, K.C. Aryan, called “neglected art” of India, referring to all those folk and tribal art forms considered almost insignificant compared to the ancient classical art. In 1968 the American scholar Stella Kramrisch organized an exhibition called “Unknown India”, referring to the villages and numerous tribes which occupied its vast territories. As early as 1916 the Victoria and Albert Museum had acquired a certain number of Kondh bronze figures, but the true discovery or rather rediscovery of this art was prompted by this new approach to Indian art. In 1977 Arts of Asia published the first academic paper on Kondh bronzes (Barbara Boal, Kondh Bronzes) followed by more studies and by a number of exhibitions that brought them to the attention of a large public (1980 Rietberg Museum in Zurich, 1985 MET in New York, 1988 Setagaya Art Museum in Tokyo).

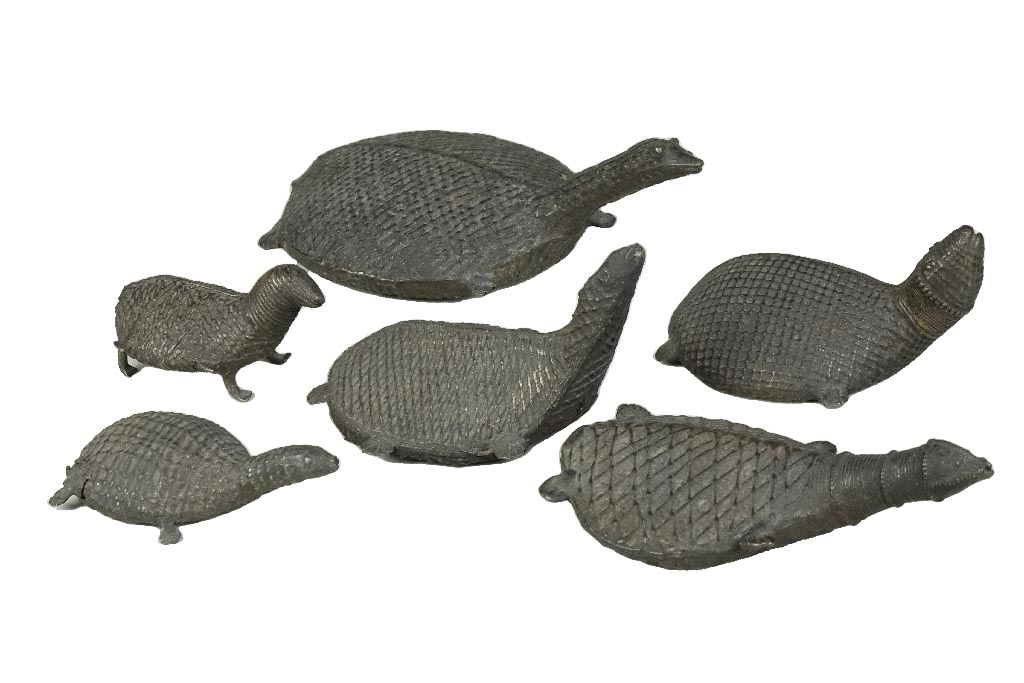

But what makes Kondh bronzes so special that they are celebrated in the field of primitive art, both Indian and foreign? For one thing the technique with which they were and still are manufactured, then their multiple uses and meanings, and lastly their special aesthetic quality. Technically these figures are made using the “lost-wax” process, an ancient metallurgical practice used both by other indigenous tribes and by traditional Hindu workshops. Kondh bronzes, however, reveal an even more complex technique, for they are wholly covered with thin wax threads (which become metal when the cast is made) creating a network that looks like a texture, thus making them unique and immediately recognizable.

Another interesting aspect is that these statuettes were not and are not manufactured by the Kondh themselves -who consider any activity other than farming and hunting as dishonorable- but by artisans belonging to the class of Hindu “untouchables” living on the outskirts of Kondh villages. Rigid taboos forbid unions between the two groups, but a century-long coexistence created an empathy that enabled the Hindu outcastes to become the interpreters of the Kondh imagination and to represent it as their own.

The Kondh religion is connected with the cult of nature and has no divine images. Indeed the two main deities, Bura Pennu, the sun-creator and Tara Pennu the mother earth goddess who taught men how to survive (to her human sacrifice was originally made, later replaced by buffaloes) are never depicted. Offerings to these two progenitors are celebrated in the village center before an altar of sorts, constituted by three simple stones (the symbols of two parents and a son, the proto-ancestors of the Kondh). These bronze figures representing the world of the Kondh are placed around the altar—those of animals show the world of nature, while the human ones incarnate the ancestors who created and preserved the tribe history. The figures of ancestors are gathered in a basket and placed close to the hearth, the real and symbolic heart of the family, and in fact the smoke of the fire covers them with a black patina common to all Kondh bronzes. Only on the occasion of disease, clashes with other tribes, or community or family problems are the statues taken outside and consulted through special rites. However, the most common use of bronzes is to be part of the dowry that a bride brings to her husband’s family in which she will live. The preparation of presents, which besides the statues also includes other bronze objects of daily use, may take years and is related with the family rank and their wealth. On the wedding day the dowry -like the presents made by the groom- will be exhibited for the guests, who will inevitably make their comments. This tradition is nowadays lost, superseded by gifts of modern and also technological objects which are much more desirable for the young couple than those statuettes covered in soot, but which nevertheless continue to be manufactured as a form of tribal identity and for commercial purposes.

It is these bronze figures, rather than words, which introduce us to the world of Kondh art. Isolated by an impenetrable jungle, having only occasional contacts with other, often hostile ethnic groups, their reality has always been the nature in which they were immersed, a mysterious and therefore magical environment where fierce and docile animals outnumbered humans. For centuries they hunted them, but also observed them until they came to know their character, so that some animals became totemic emblems of the various clans forming the tribe. And when the first ancestor statues were made that sort of Noah’s ark that is the Kondh bestiary could not be ignored: an endless array of deer, gazelles, buffaloes, tortoises, tigers, scorpions, frogs, crocodiles, peacocks, wild boar, snakes, birds and even elephants (which the Kondh only saw when the British arrived in 1835). These animals, whilst remaining semi-realistic (which generally makes them recognizable) undergo a transfiguration combining reality and imagination, with at times caricatural, humoristic and even surreal results: the three-headed tortoise, the four-legged fish, the human-headed scorpion… The same happens with human figures in which temperament transpires more than form, or in some cases an ideal beauty transcending anatomical proportions—evocative rather than descriptive images.

The spontaneous simplicity of these figures is added to by the mesh of thin metal wire that covers them, creating a contrast of light that animates them like a living presence. That’s what the mystery and beauty of Kondh bronzes is all about.

All the exhibits are from Dr. Giuseppe Berger’s collection. They were bought in the 1980s and 1990s and date from the first half of the 20th century.

No Comments