21 Jan Chinese Portrait Painting

by Isabella Doniselli Eramo

For a painter, striving for spirit resonance chiefly means creating a special harmony between his own soul and the subject’s in order to represent his spirit through forms, capturing the vital flow which animates them. This is the first of the ‘Six Fundamental Principles of Painting’ codified by Xie He, a painter and portraitist of the 5th century A.D. who includes ‘spirit resonance’ among the values that must inform any work of art worthy of this name.

This fundamental principle also applies to the particular genre of portrait painting, which has a long tradition in China despite having been grossly underrated for a long time, also due to the movement of ‘breaking with the feudal past’ which, starting from the 1950s, caused many works of art to be destroyed or sold off and thus dispersed on the international art market. It is only recently that a renewed interest by collectors, scholars, and art lovers sparked an unprecedented number of in-depth studies.

Origins of portrait painting

Recent studies directly connect the portrait tradition (Chinese xiezhenhua, literally: ‘real life drawing’)1 with very ancient mural paintings or paintings on cloth,2 and particularly with tomb paintings of the Han dynasty (206 B.C.-220 A.D.) and of the Tang (618-907). Unfortunately, the number of paintings that have come down to us is too scarce to enable an historical study of the evolution of portrait painting from its origins. Chinese critical studies are also lacking, for, starting from the Song dynasty (960-1279), the refined scholar-artists of the best Chinese tradition always considered portraiture as an inferior artistic expression little worthy of analysis and study.

The few elements we have, however, enable us (also by analogy with tomb paintings of the same age) to infer that the oldest portraits usually showed the subject in full length, standing in full natural light, without any chiaroscuro or three-dimensional effects, on a blank background in order to give prominence to the figure. The figure was outlined with few lines accentuating the elegance and ‘heroic spirit’ of the subject. The real aim was to transmit to future generations the best qualities of the persons depicted in order to turn them into models of social ethics. For this reason, too, the subject was preferably caught in the act of performing a specific action within the context of a clearly identifiable historical fact, almost as if to provide visual proof of his taking part in the event.

From the very beginning the artist sticks to the principle of chuanshen, i.e. ‘showing the soul’ or ‘conveying the spirit’ of the subject. This often justifies partially sacrificing the faithfulness and detail of the physiognomy. Chinese portaiture is thus never a mere transcription of physiognomic characteristics, but rather a combination of physical fidelity and of what the painter sees as the intimate being of man, based on the knowledge of his life and on the artist’s own intuition.

Starting from the Tang dynasty a preference for landscape painting and flowers or animals begins to form. This tendency will gain ground with the cultural hegemony of aristocratic scholar-artists who, from Song times onwards, will assert an absolute pre-eminence of flowers and birds in painting, and even more of landscape as the only true pictorial art worthy of this name. This attitude will continue during the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties, and it will in fact relegate portrait painting and its artists into a closed niche, almost an enclave of ‘sons of a minor god’ within which the peculiar specialisation of ‘ancestor painting’ will evolve.

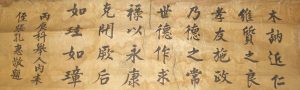

However, within the intellectual élite of ‘literati-painting’ the pleasure survives of portraying themselves intent on their favourite occupations of reading or contemplation of nature, or of depicting artists and poets of the past in order to keep their memory. But this is sui generis portraiture, aimed at suggesting to the observer the spiritual nature of the person portrayed and the ideal of artistic contemplative life that unites both painter and subject. Its preferred technique is monochrome ink or very faint colours, essential, almost calligraphic brush strokes reminiscent of chan (zen) painting conventions. The painting is often complemented by poems and dedications. Calligraphy itself is a form of art in the tradition of Chinese scholars, or rather it is Art par excellence, along with painting and poetry, which are closely linked as artistic expressions typical of the ‘literatus’, of the aristocrat of culture and erudition, member of a true artistic-cultural élite. In the Chinese custom, the painter had the possibility of adding a poem to the painting in order to complete its content and to better define the states of mind he wished to express with the image. Alternatively, other scholars or collectors would add their thoughts and verses written in nice calligraphy, as a gesture of homage to the painter or to witness their participation to his feelings.3 With the Yuan (1279-1368)—the period of Mongol rule which, under the influence of the governing foreign class culture sees a relaxation in the hegemony of the scholarly tradition’s aesthetic canons and idioms—a relative revaluation of portrait painting can be observed, with more attention for the physiognomic study and a more careful modelling of faces and expressions, while the rendering of clothes and fabrics is achieved with a few essential lines. In the same period a first faint distinction starts to be made between figure painting and commemorative portraits, and the first few names of celebrated portrait painters are recorded. To one of them, Wang Yi (14th century), we also owe the first theory codifying the standards and techniques of portraiture understood as xiezhenhua (real life drawing). These idioms, techniques and styles will then be refined in later times, accompanying the great flowering of portraiture between the 16th and the 19th century.

Informal portraits and Ancestor portraits

Just as the Taoist and Buddhist thoughts—with their implication of love for nature and for all living beings and with their ideal of nature and man partaking in the same emotional states—are the soul of landscape painting and flowers, birds and bamboo painting, so the Confucian culture fosters the development of portrait painting, providing a background of ideals and thought to this painting genre. Indeed, on the one hand the Confucian virtue of filial piety encourages the depiction of exemplary persons from the past in order to make them a model for new generations; on the other it inspires the custom of portraying one’s own ancestors as a sign of deference within the practices of the cult of ancestors.

Between the 16th and the 17th century two different styles of portraiture begin to take form. The scholar-painters like to paint the subjects in an environment expressing their spirit, character and tastes. Later on, the wealthy bourgeoisie will copy this style in its own fashion, and it will become common practice for a son to commemorate his deceased parents by commissioning paintings depicting them busy in their usual favourite occupations. But also an important family event, an anniversary, a turning point in a career, can be remembered and solemnised with a painting of this type. In parallel the school of the more properly commemorative portrait develops, with the function of recording the ancestor’s image for ritual purposes. These paintings are used to open the funeral procession, and in some cases can even replace the bier itself (nowadays, in funeral rites still connected with tradition, this function is performed by large photographs of the deceased). The portrait is then kept in the family and displayed on particular occasions connected with the cult of ancestors. The more affluent families, whose houses have adequate dedicated spaces, may keep their ancestor portraits permanently on display behind the ritual ‘tablets’ bearing their names, in a special room where the domestic rites for the ancestors are performed. In the tradition of the Confucian-inspired ancestor cult, these tablets (which may be of wood, ivory, jade or other more or less precious materials) have the important function of representing the spirit of the deceased, and each family keeps them in a dedicated place in the house where they are the object of care and rituals in honour of the ancestors.

The ancestor portrait, due to the commemorative and ritual purposes which originated it, has a substantially different basic approach compared to the informal portrait. In fact, the latter is often an idealised depiction of the subject, set in a narrative scene, and it implies a significant amount of creativity, imagination and sensitivity on the part of the artist, who must be able to capture the deepest nature of the person portrayed and convey to the observer a general idea of his life, habits, tastes and affections,

Conversely, the ancestor portrait’s primary function is to fix the subject’s image for ritual purposes, hence it tends to focus on the face physiognomy and on a series of external details, which become highly symbolic canonical features, in order to provide as much information as possible about the ‘public’ aspect of the subject: character, moral qualities, status, role, rank.

It is generally a vertical scroll that can easily be hung, showing the ancestor in full-length, in a rigidly frontal and symmetrical stance conveying a sense of hieratic immobility. “The ancestor,— write Jan Stuart and Evelyn S. Rawski(4)—seems shrouded in stillness, removed from all worldly activity, and never performs a gesture more active than fingering a costume accessory: […] an iconic convention meant to inspire awe and devotion. […] emphasis is laid on the fact that he is finally out of a human state and has achieved a supermundane level of existence […]. The emphatically static, rigid pose of the sitters manifests this rarefied, imperturbable state of being.”. The subject wears formal clothes, with well-visible symbols of rank and social function. The face, placed at the image’s focal point, is faithfully depicted with a painstaking care for details. The body, on the other hand, is summarily represented, almost as if it were just a pretext for showing the formal dress and the rank insignia. Usually, especially in the case of emperors or their consorts, imperial princes, high-ranking dignitaries, the portraits were made from life, with the subject sitting for the preparation of his official portrait. Outside of this privileged élite, however, it was not uncommon for a posthumous portrait to be ordered by the descendants, on the basis of other images and of the personal knowledge the artist might have had of the deceased.

From Ming to Qing

Portrait painting becomes established in China, albeit as a minor art, chiefly with the Ming dynasty, and starting from the 16th century it reaches the peak of its flowering, in parallel with the maximum specialisation of the artists. At court a permanent painting studio is set up to allow members of the imperial family to be portrayed, but also outside the court the ‘fad’ for portraits spreads and portrait painters make their fortune. Regional styles also start to take shape, with different idioms and techniques.

In the first decades of the Ming dynasty, for which unfortunately very few examples have survived, strong ties still exist with the older Song and Yuan portraits: the subjects are painted in a conventional way, more often standing or riding a horse rather than seated, with the body slightly turned to one side, while the background is left completely blank.(5)

Starting from the reign of the emperor Xuande (1426-1435) a new stylistic phase of portraiture begins: the subjects are shown frontally, seated on an accurately reproduced throne, with great attention to the smallest detail of the decoration. The facial expressions are rigid and ‘starched’, their gazes lost in a supermundane dimension. Imperial portraits particularly emphasise this iconic aspect, almost as if to affirm the imperial role over the subject’s individuality. The background is now treated with faint colours and enriched by the presence of simple furnishings for everyday use, like small tables and stands with flower vases and desk accessories or tea sets; but it becomes completely empty again with the reign of Wanli (1573-1619), which ushers in the final phase of the dynasty. There are often secondary personages, servants or maids, behind the subjects or in the background, in the act of serving tea or proffering symbolic objects.

The most apparent innovation in imperial portraits of this period is the replacement of the throne with a wooden chair sumptuously draped with a cover, or, for rank officials, with an animal skin (tiger or leopard). The decorative motifs of the carpet, on the other hand, appear much simplified, and the carpet itself tends to become the prerogative of the aristocracy, whereas the scholars prefer to do without it, and commoners are not entitled to it anyway.

The portrait dress, too, reflects this changed approach. Emperors and members of the imperial family are now portrayed in formal dress, whereas scholar-officials prefer an informal attire

The use of multi-generational portraits also becomes increasingly popular. In this case the men generally wear informally, while their wives use formal dress, complete with the consort’s rank insignia. The paintings of couples (husband/wife), or of three people (husband/two wives) also gain popularity.

Within the Ming portraiture (and notably late-Ming) two different basic techniques exist: the goule or ‘outline’ method, which prescribes thin outlines and light layers of colour wash, with repeated applications of colour to heighten shaded parts (this method was particularly common in the northern regions), and the method of the Jiangnan school (similar to the old meigu or ‘boneless’ method, that is without outlines) more common in the southern regions, which only uses grades of colour to define lineaments and expressions, achieving remarkable volumetric and perspective effects.

The Manchu-originated Qing dynasty is represented by a higher number and a greater variety of portraits that have come down to us, which makes critical appraisal easier.

Initially it inherits the two basic techniques of the Ming predecessors, i.e. the goule method and the Jiangnan method, which maintain their traditional distribution in the north and south respectively. The paintings exhibited are connected with the Jiangnan school method, and they also show its evolution in time. With the reigns of the three emperors Kangxi (1662-1722), Yongzheng (1723-1735), and Qianlong (1736-1795), representing the dynasty’s apex of power and artistic-cultural aperture, the southern style proves to be quite receptive and open to the influence of Western painting, brought in particular by the Jesuit missionaries, who also employed their artistic skills to fulfil their mission of cultural mediation and evangelisation. Shading and light are treated in a more realistic way, obtaining completely new volumetric effects. The only point of detail on which the Chinese artists remain firmly tied to their more genuine tradition is the use of a frontal light source (or from above), whereby the subject’s face is always in full light. This general setting remains virtually unchanged until the last decades of the dynasty, but within it five different regional styles originate:

Beijing style: painting on silk, thin facial outlines, solemn and rigid expression

Shanxi style: Painting on cloth, face painted separately on paper and pasted on the body, which, like the setting, is painted in bright colours

Jiangnan style: painting on paper, no contour lines, simple, accurately represented dress

Guangdong style: on paper, colourful with sumptuous, accurately ornamented backgrounds

Fujian style: on paper, rigid expression and painstakingly decorated costumes

The size of Qing portraits is relatively standardised, while the range of subjects includes portraits in court dress, informal groups, half-length portraits and multi-generational groups. The latter represented in most cases a cheaper alternative to individual portraits, thus bringing them within the reach of less wealthy families. They normally depicted from two to five generations, but, above all in the northern regions and in more recent paintings, the number of people portrayed could reach several dozens. The high number of subjects and the limited size may sometimes be detrimental to the accuracy in the rendering of the individual physiognomies. This is why the single figures often bear their name on the collar or on the shoulder, or written on a ‘tablet’ placed beside each of them. It also happened that sometimes, when the painting was sold, the descendants ‘erased’ their ancestors’ names as a form of reservedness: thus it is not unusual to find ornamental motifs hastily painted on the costumes in order to conceal the ideograms of the name, or to see ‘erased’ name tablets or painted white.

The background, which at the beginning of this dynasty clearly betrays the Ming legacy with the depiction of tables, other items of furniture and carpets, tends to a dramatic simplification toward the middle Qing, reaching by the late Qing the completely blank background typical of the portraits in court dress . By contrast, in multi-generational portraits the background is tendentially much more complex and full of furniture and servants. There is often an architectural element framing the family group, with the same function as the pavilion for the cult of ancestors whenever the house did not have enough room to have a real one. Furthermore, since these portraits were meant to be exhibited in one room, the furniture shown in the background tended to harmonise with the room furniture, achieving in some cases a true continuity with the real room. In the southern regions a trend develops towards an increasing complexity of the backgrounds, overburdened with decorative motifs and ambient details, which tends to generalise in the last years of the empire.

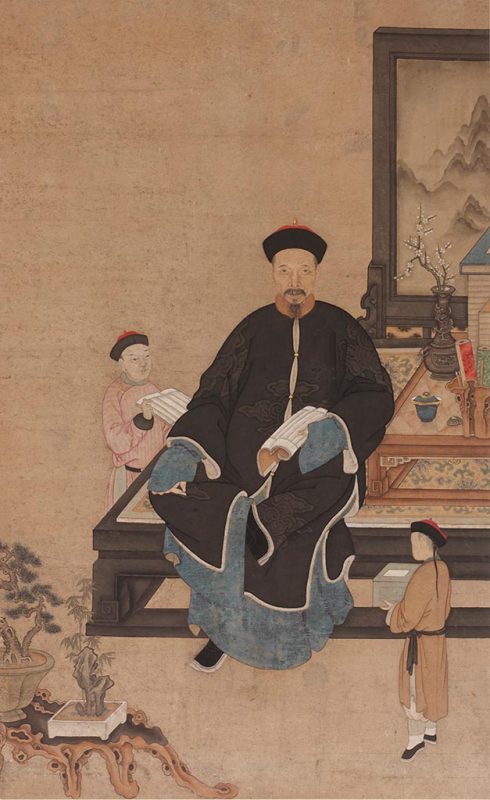

Well attested for the entire Qing period is the style of the so-called informal portrait (as the portrait on this page) which, inspired by the scholar portraits, depicts the subjects in their daily life, with meticulous care for the face lineaments and expressions and a masterly use of shading and colour without outlines. Conversely, the body, dress, setting details, and secondary figures are depicted in a very traditional fashion.

Towards the end of the dynasty the number of portraits showing the subjects busy in their daily occupations rises dramatically, due to the increasingly popular use, also within the middle classes of the ‘new rich’, of commissioning both ancestor portraits and informal portraits for special occasions. The evolution of portraiture from an élite to a mass production brings about on the one hand a proliferation of scholar-artist works for the aristocratic-cultural class, accompanied by the valuable production of skilled court painters, often, but not always anonymous. On the other hand a large number of portraits is made by more modest, skilful artisans who, also in order to satisfy the considerable number of orders, end up producing portraits for ritual use that become rigidly and repetitively standardised. But this is a recent development (late 19th, early 20th century), when, after the reign of emperor Xianfeng (1851-1861), the increasing popularity of photography and the development in Guangdong of a burgeoning export trade of specially made oil paintings introduce a number of stylistic innovations in the portrait tradition. The use of touching up photographs with water colours, especially to render the colours of court dresses, steers commemorative portraiture in a new direction, and on the threshold of the 20th century it extends to photography. Meanwhile, with the fall of the Qing dynasty and the beginning of the republican age, the fashion of charcoal drawing gains popularity: a new technique seems to push Chinese portraiture out of the rut of tradition and to connect it to a ‘globalised’ artistic circuit.

____________

Note

1 In fact the Chinese language offers several ways of designating what we simply call “portrait”: chuanshenhua, literally ‘vivid portrait’, chuanzhenhua, literally ‘true portrait’; xiezhenhua, ‘real-life portrait’; xiezhaohua, ‘portrait from the original’; rongxianghua, f’ace portrait’. The choice of one term or another often depends on the historical period, the geographical location, the purpose of the painting, the aim the artist or commissioner had set himself.

2 Shi Gufeng, in Art of Portrait of Huizhou, Anhui Art Publishing House, 2001, specifically mentions the silk painting “The Jade Dragon Going to Heaven”, unearthed from a Chu tomb dating from the Warring States period (475-221 B.C.), and the Han-period silk painting found in tomb No. 1 at Mawangdui as two of the most significant examples for the later developments in portrait painting.

[3] Chinese writing, which originated in the 2nd millennium B.C., initially evolved into different local or regional styles, among which the one called ‘of the great seal’, also used for inscriptions on bronze ritual vessels, emerged for its completeness and elegance. With the unification operated in the 3rd century B.C. by the first emperor of the centralised empire, Qin Shihuangdi, the script ‘of the small seal’ was codified as the official writing, still used nowadays for seals and decorative inscriptions. Over the centuries (and above all with the introduction of paper in the 2nd century A.D. which opened totally new technical and literary possibilities, making calligraphy a true art) Chinese writing underwent an artistic and aesthetic development which brought it to levels of refinement unimaginable in the West, giving rise to a number of writing styles: legal (lishu), regular (kaishu), cursive (xingshu), minute (caoshu) that originated in Han times (206 B.C.-220 A.D.) and which are the ones more widely used today.

4 Jan Stuart, Evelyn S. Rawski, Worshiping the Ancestors, Chinese Commemorative Portraits, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC, 2001, pp. 52 ff.

5 Simon Kwan, op.cit. Chinese Portraits, Muwen Tang Fine Arts Publication Ltd, Hong Kong 2003

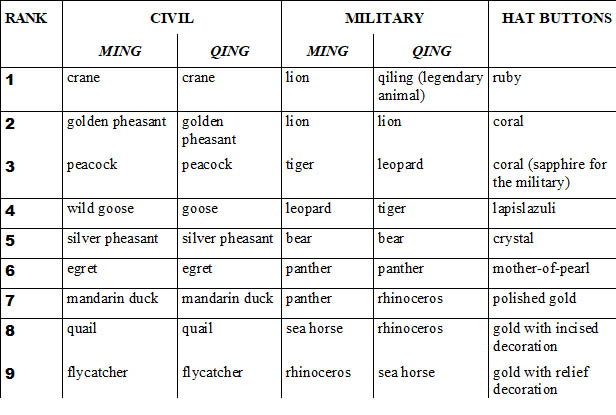

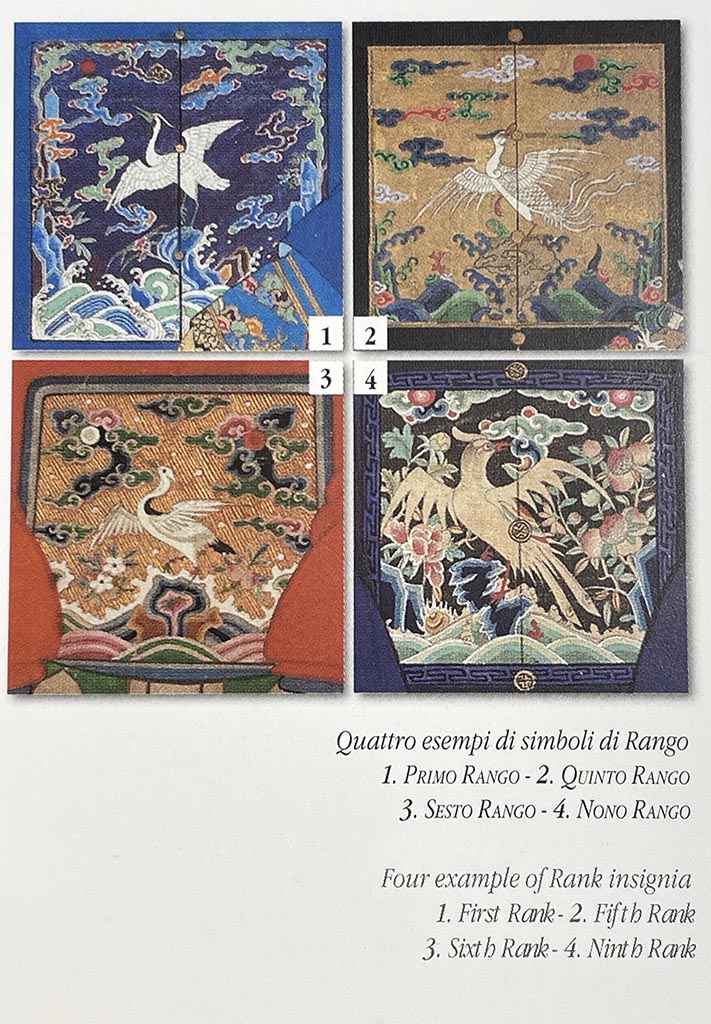

Rank insignia

The badges identifying the rank of functionaries—the civil and military officers known in the West as ‘mandarins’—are indicated by symbols embroidered on the front and on the back of the ‘bufu’ and by ‘buttons’ on top of the headgear. These buttons are of different materials and colours depending on the rank. The embroideries represent series of animals, usually birds for the civil officials and four-footed animals for the military ones.

The most prestigeous rank is the first, but even obtaining the more modest ninth rank is considered a great achievement, for it implies in any case passing a series of difficult and highly selective state exams testing the candidate’s thorough knowledge of classical Confucian texts.

Left. Example of semi – formal Qing female court dress

ISABELLA DONISELLI ERAMO

Vice-President and Coordinator for the Scientific Committee of the ICOO Institute of Culture for East and West in Milano.

Author of several studies and articles about the subject of China meeting Europe and history of Jesuit Missions in China.

Among her publications: “Glances from the Past, Chinese Portraits from Ming to Qing” (Renzo Freschi Oriental Art); “Giuseppe Castiglione, a Milanese artist in the Celestial Empire (Luni Editrice); “The Dragon in China-History of an icon” (Collana Biblioteca ICOO, Luni Editrice),ITALIAN ONLY.

Descriptions

by Elettra Casarin

Elettra Casarin, sinologist, expert in Chinese costumes and fabrics, as well as in ancient western textiles is the author of numerous studies on ancient oriental and Western textiles. She is also in the team of the Educational Department at the Museo di Palazzo Ducale in Mantova and at the Museo del PIME in Milano, designing educational programmes and activities.

LIKE A MASTERPIECE OF JADE

Qing dynasty (1796)

ink and colour on silk

172 by 103 cm

Being taciturn and honest to a fault

Is an innate virtue of your character

In public office you serve everyone like family and friends

As if it were a common attribute demanded of any good man

Such integrity will reward you generation after generation

May you be blessed with good health and longevity

In time there never was and never will be such a masterpiece of jade as you

Respectfully written by the paternal nephew and titled scholar of the Year of Bingchen (1796) Zhang Konghui.

Inscription removed from the painting and pasted on the back

The good wishes expressed in the dedication warrant the idea that this portrait was painted from life, as a homage from Zhang Konghui to his uncle, in the observance of the Confucian practice of filial piety. The painter, who followed the canons of the Jiangnan school, devotes the same degree of care to both the depiction of the face, strongly characterised, and of the sumptuous formal court dress (chaofu) in an effort to express the official’s status, the fifth civil rank, as well as his personality.

The humble and serene expression of the face, particularly the lips hinting a smile, refer to the profound wisdom of this official, capable of remaining silent when someone is mistaken, or to use his mouth only to pronounce a verdict of truth. His benevolent gaze confirms his openness to anyone seeking his advice, and thus proves his altruistic nature.

Moreover, the reference to jade in the dedication is not casual, it is a clear allusion to the five virtues of this stone, metaphorically compared to those of the official.

The chaopao featuring the dynamic front-facing dragons and the blue damask bufu decorated with motifs known as ‘the scholar’s treasures’, on which the superb mandarin badge stands out, with a profusion of gold applied on the back of the silk support, make the dignitary’s costume simply superlative.

Detail

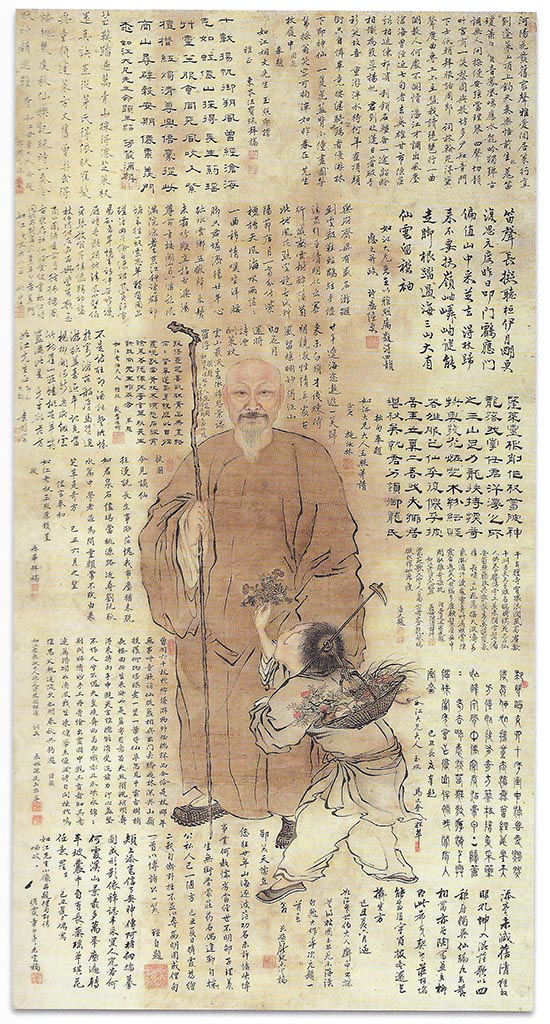

IN HONOUR OF MASTER RUJIANG

Qing dynasty (19th c.)

Ink and colour on paper

122 by 62 cm

In Honour of Master Rujiang

After twenty years out on the vast sea,

you come back laughing and still young.

Wiser but always innocent,

your pure heart as clear as a mirror.

The way of getting along with people and with yourself

is to be honest and sincere,

following the old Chinese tradition.

Playing and travelling in the many-coloured world,

you obtained something treasurable in return.

So now, may you lean on a stick

to climb the cloud-capped mountains,

where perchance you will find the place where the heavenly is.

[Poem in Kaishu writing at centre over the head]

Incredibly modern, this painting is a tribute to master Rujiang by his friends, students, and disciples, on the occasion of his retirement from work. In the space left free by the painter who, inspired by the tradition of chan (zen) painting, executed his old master’s portrait with quick brush strokes of monochrome ink, applied with light touches of the brush, sixteen dedications and poems were written in different calligraphic styles by those who knew, appreciated, and loved him most during his long and honoured career. Placed at the composition centre is the protagonist Rujiang. Clad in a simple robe, the elderly scholar learns on a knotty stick, while a young boy offers him flowers from a basket full of fruits and well-auguring herbs with a strong symbolic significance like peaches, mushrooms of long life, and pine twigs. The dedications confirm that the painting, in addition to inspiring the composition of the lyrics, also provided the basis for a literary divertissement in which the master’s friends took part in a contest of composition, style and calligraphy -an art which, along with music, painting and chess playing, was one of the “four occupations” of the scholar. The poems by Old Lu and by Shi Rulin revolve around the metamorphic power of the stick and of the herbs, as magical elements capable of ensuring Rujiang’s immortality.

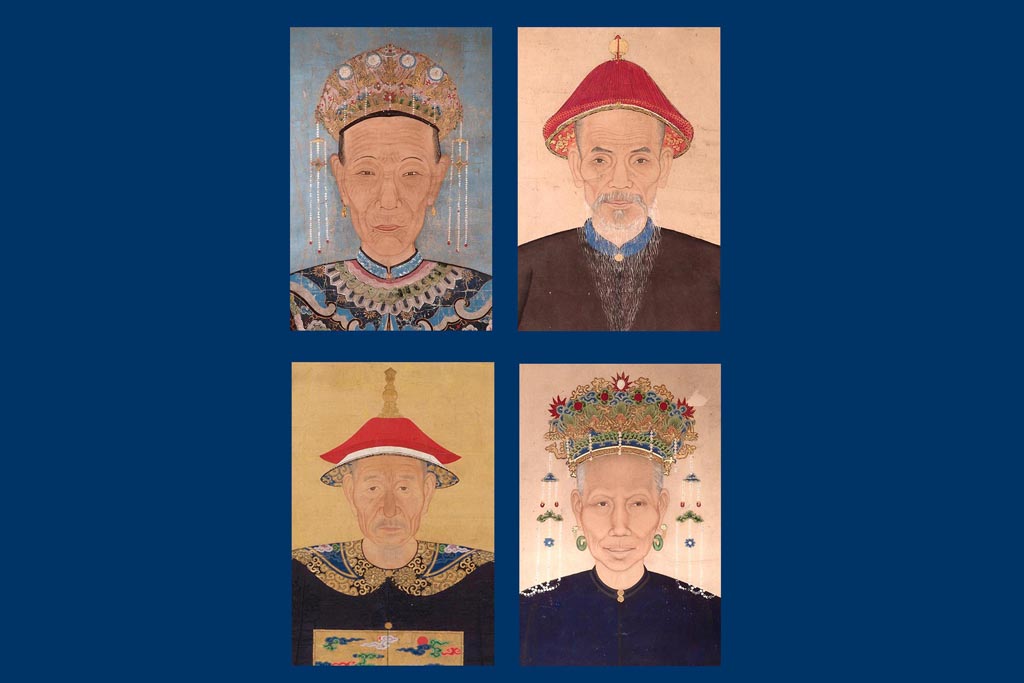

THE GENTLEMAN HE YONGHUA WITH HIS CONSORT LADY WANG

Qing dynasty (18th c.)

ink and colour on silk

100 by 79 cm

The couple sit inside a pavilion, on wooden jiaoyis placed on a carpet with a ‘tile’ design which, also thanks to the painstakingly depicted, opulent costumes, contributes to the dynamic effect of the painting.

The man wears the semi-formal court dress (jifu) with the mangpao partially hidden by the overgarment bearing the insignia of the ninth rank—the flycatcher; the same emblem is also applied, reversed, on the wife’s precious dress.

A maid hands the lady a tray with three ‘Buddha-hand’ lemons, while a youth gives the man a painted scroll. Behind the persons represented, symmetrically placed on a long altar table with the typical upturned ends, are two ancestor tablets bearing the couple’s names and two vases with a craquelé pattern—one blue containing a blossoming branch next to the lady, one white containing a branch of red coral and a painted scroll next to the official, to indicate his intellectual qualities.

On the background, lining the wall, are eight different paintings of mountain landscapes, made of vertically pasted panels.

The composition is full but balanced, thanks to the symmetrical arrangement of persons and objects and to the colour scheme which, from the colourful base with the carpet and the costumes, attenuates towards the top, dominated by the sober sepia monochrome of the background.

The portrait can be assigned to the regional style of Shanxi; it is painted on silk, the faces being executed separately on paper and then cut out and pasted onto the main painting.

The work was badly damaged, but underwent careful restoration: apart from cleaning, which brought the brilliant original colours back to life, some parts of the painting had to be touched up, like the young attendant’s hand and some areas of the upper section.

HUSBAND AND WIFE WEARING A MANGPAO WITH DRAGONS

Qing dynasty (19th c.)

ink and colour on paper

118 by 89 cm

The portrait shows husband and wife both wearing the mangpao with four-clawed dragons, blue for the husband and red for the wife. Contrary to the Ming custom, when the mangpao could only be worn by imperial permission, in Qing times it became an integral part of the code of formal wear, a sort of festive dress worn, as in this case, by all officials and their wives.

It is difficult to ascertain the rank of this couple, since none of the two wears the overgarment with the square mandarin badge; only the official wears the winter court hat with the typical upturned fur brim hemmed by scarlet silk threads. He also wears a cape and a belt embellished by two lion-shaped gold clasps from which two white silk straps are suspended.

The couple sit side by side, very close to each other, the wife to the husband’s right, slightly set back as requested by tradition, on two simple wooden armchairs covered respectively by a green silk fabric with gold floral motifs and by a tiger skin.

While both costumes are rendered with the same level of detail and realism, the faces are treated in different ways. The artist, using the technique of ink shading, lingers on the facial features of the husband, even heightening some traits like the cheekbones (quan) which in the Chinese tradition, due to the homophony with the word for ‘power’ (quan), are a sign of high authority, while the lady’s face is painted in a much shallower and anonymous way.

The almost relaxed stance of the bodies, but above all the man’s feet in an asymmetric position, safely date this work to the Guangxu period (1875-1908): before that time, in fact, this posture would not have been acceptable in an official portrait.

SITTING IN THE PAVILION OF LOVE AND BENEVOLENCE

Qing dynasty (19th c.)

ink and colour on cloth and paper

99 by 72 cm

A gentleman is depicted inside the pavilion “In memory of the parents”, as reads the inscription on the roof beam, which indicates that this is a posthumous portrait (jiebo) commissioned by his descendants to honour his memory. Furthermore, the verses chosen for the two pillars are closely linked with two of the Confucian virtues metaphorically considered the true pillars of the family: the practice of filial piety and the benevolence of superiors towards their subordinates. The poetic text reads in fact: “As vast as the boundless sky is your love” (righ-hand pillar), “So deep is your benevolence that it will be impossible for your sons to pay it back” (left-hand pillar).

The work is a typical example of the Shanxi regional production, characterised by the face painted separately on paper and then cut and pasted on the painting, usually made on silk or another fabric.

The gentleman is set in a landscape rendered with a lively chromatic composition, but this naturalistic context is only an appearance, for in fact it reveals a high level of symbolism; hence the painting cannot be read at a figurative level only, its numerous allegorical references must be caught as well.

Firstly, the animals in the garden, while clearly recognisable as crane and deer, incarnate a well-wishing message: the deer stands for reward and, like the crane, is associated with longevity thanks to its ability at finding the sacred mushroom of immortality.

The pine tree protecting the pavilion where the scene is set is another symbol of longevity and tenaciousness, for it survives the cold and never sheds its needles. Along with the crane, the pine tree symbolises the last years of a long life. Lastly, crane, deer and tree are often defined as helu tongchun, they symbolise the wish for an official promotion in spring.

The almost relaxed stance of the bodies, but above all the man’s feet in an asymmetric position, safely date this work to the Guangxu period (1875-1908): before that time, in fact, this posture would not have been acceptable in an official portrait.

THE SPIRIT OF THE SCHOLAR

Qing dynasty (19th c.)

ink and colour on paper

124 by 77 cm

This painting is a significant example of an informal portrait, in that it depicts a gentleman in a context characterised by elements revealing his tastes and attitudes. Specifically, the objects in this scene are accurately selected to underline the refined tastes of the scholar—notably the imposing dreamstone behind him, the exclusive brush container with scrolls and the natural briarwood table carrying two bonsais, a pine tree and a bamboo. These trees, along with the plum branch in the vase, are also known as the three friends of winter and symbolise friendship and the ability to overcome obstacles with the help of a friend.

The true protagonists of this work are the books arranged on the table, held open in the hands of the scholar and of his attendant, and also in the book case held by the other youth.

The scholar, whose traits are relaxed and serene, is portrayed in an informal, easy stance, sitting on a kang with the right foot resting on the left knee. The simple robe, too, highlights the private dimension of this image, the only evidence of his official status being the winter court hat.

The thin column of smoke rising from the incense-burner gives the impression of a live scene. The composition is balanced thanks to a harmonic alternation of full and empty forms which appear quite modern.

Contrary to what is normally the case in ancestor portraits, here we see a convincing application of the rules of perspective. The physicality of the bodies and elements is accentuated by the use of chiaroscuro, and thus the subjects appear set in a real environment, not projected into a supernatural state. This kind of portraiture, inspired to the production of literati-artists, is not meant for ritual purposes, rather it aims at remembering a dear one, immortalising him busy in his favourite occupations.

AN ASSURED DESCENDANCE

Qing dynasty (19th c.)

ink and colour on paper

130 by 62 cm

This painting is a typical example of an informal group portrait of the Qing age. The protagonist is a gentleman portrayed at home, in his double role of family head and scholar, surrounded by his dearest persons and objects.

The circular arrangement of the family’s male members—the father and his three sons—reveals the sense of union and continuity, further enhanced by the presence of the crane, which in the complex Chinese symbolism signifies longevity. The eldest son holds a book in his hand, thus following in his father’s footsteps, the second-born ostentates the family’s high extraction by wearing a precious gold necklace with a bulky ornament, while the youngest son, shown with his prominent sex, emphasises the importance of a male progeny to ensure the continuation of the family.

This privileged condition of complete fulfilment is rendered by the artist with the idyllic familiar atmosphere, but also by every single detail of the gentleman, who radiates security and self-confidence. The spirit of the scholar is expressed by both his figure—the easy stance, the bright and lively eyes, the lips relaxed in a satisfied smile—and by the setting which is used to even more closely define his character.

On the table behind him the neatly arranged books stand out, encased in boxes of precious damask-silk, and next to them is a brush container with a painted scroll, a feather, and some brushes. A vase containing the mushroom of long life and a peacock feather is shown at the other end of the table.

On the background, a young woman bashfully comes out from behind a column, tenderly gazing at the blossoming branch she holds in her hand, almost suggesting a new promise of motherhood.

Wealth, well-being, culture and a male offspring define the perfect condition of the scholar’s family.

PEAN TO XINGJUE, A HEROIC LEADER

Inscription by Huang Fuqing from Huilou

Qing dynasty (19th c.)

ink and colour on silk

156 by 83 cm

To live in the fields and yet to be endowed with the military acumen of Sunzi and Wu Qi

Only you can be like that, sir Xingjue!

You were born in a barren valley

Leading a life that was no different from any farmer’s

Subject to Nature’s temper of rain or shine

But when the bandits from outside raged

The feeble-minded were all frightened and distressed

But you took it all upon yourself and went ahead

Preparing for battle night and day

As a result you were presented for commendation at general Tan’s camp

And because you stood up for your people

Your name shone in glory among the noble dynasties

You led with true leadership

And avenged the men and women poisoned by ill feeling.

The Confucian virtue of filial piety is well exemplified by the dedication at the end of the inscription which reads: “Respectful paean to uncle Xingjue, on his portrait, composed and written, with a bow, by Huang Fuqing from Huilou”.

This is in fact a homage to Xingjue who, as a humble farmer facing an imminent danger for his kinsfolk, becomes a heroic troop leader revealing the intelligence of a strategist coupled with great bravery, so that he is even compared to the celebrated Chinese general Sunzi, the author of the treatise The Art of War.

The attention centres on the face, from which radiates all the charisma, the extraordinary inner strength and high-mindedness of the protagonist. His facial features, particularly the cheekbones and temples, appear in high relief thanks to a deep shading obtained by repeated washes of sepia ink, an evolution of the Jiangnan style.

Xingjue, despite having obtained the highest military honours, remains a commoner, as also confirmed by his simple dress. His rank of military officer is only betrayed by the winter court hat terminating with a ball finial and by his boots. In the right hand he holds a fan, while with his left he is telling the beads of a Buddhist rosary, almost as if to indicate his deep spirituality.

PORTRAIT OF TANG YIN

Anonymous painter

China, Qing dynasty

19th century

Ink and colour on silk

Cm 156 by 115

This talented anonymous painter perfectly captured – according to the Chinese idea of the portrait – the spirit of the celebrated painter Tang Yin.

Set in a romantic natural scenery, Yin sits beneath a large rock full of cavities from which bamboos stick out; a large inscription is carved in the rock. Holding a tea cup and a brush in his hand with long fingernails – a sign of distinction – Yin seems intent on the creation of what he does best: poems and paintings. Around him are the distinctive objects of the literati: numerous books, brush pots with various brushes, a string instrument, precious bronzes, sweet perfume burners, but also more down-to-earth implements for his daily use and pleasure: a teapot, a bottle of wine, a bowl of food and one full of peaches (a symbol of longevity), a fan and a fly-whisk.

On his head Yin wears one of the famous Chinese hats used by important personages, made of various layers of a stiff net, very thin and light. The body posture is relaxed; his gaze, completely absorbed in his thoughts, conveys sweetness, serenity, and an intense spirituality. In fact, despite his vicissitudes, in his adult life Yin embodies a philosophical attitude of detached, serene acceptance that characterized him from a certain point in his life onwards.

Only one poem by Tang Yin appears in the painting, signed and placed parallel to the rock inscription:

“From the stars of the sky I take a poem/Capturing the moon dragon

I soar to the Milky Way/Flying among countless faint lights

I seal the poem on the green moss-covered stone stele/In the summer of the Xinwei year”

The other poems are the work of various poets. Starting from the top left, the first vertical one is signed by the poet Yu Ran:

“Slightly drunk

I caress the old cup of wine

The wind blows and brings to me

The verses of a poem

And the thought that the dragon will come

Rushing after the wind”

A vertical poem right next to it is signed by Shu Ti:

“I live alone near the Peach Blossoms harbor

And here is my best self-portrait:

Detached from the things of this world

I live peacefully on the earth like an immortal

I never leave any wine on the table

If I don’t drink it, who should?

When inspiration comes I read my poems out loud

I envy Tang Yin very much”

The horizontal poem right underneath, signed by the courtier Ji Huang, proudly states the following about the category of poets:

“The best poets in the south of China/Are free men/And they do not follow rules

When they call on Peach Blossoms harbor/They drink and laugh together

If inspiration catches them they are lifted to heaven/They raise their cups and drink like the sea

With their brush they write/Many good sentences and the blowing wind

Brings the scent of flowers/But they do not just drink

They also talk politics/They praise the Buddhas

They close the door to talk in private/And even the emperor envies them”

A SCHOLAR WITH HIS FAN

China, Qing dynasty

18th-19th century

Distemper on paper

82 by 65.5 cm

Seated at the base of an old pine tree trunk twisted by time, the scholar wears a comfortable informal garment and holds a peacock-plumed fan in his thin hands, typical of those who do not do any material work. On the table, a blossoming peony grows in a vase, while a finely carved ruyi scepter simply rests on it. Beyond the steep bank, a river flows peacefully. On the opposite bank a blossoming prunus tree can be seen in the distance. It is a rarefied landscape in which only the soft colors of the scholar and the objects that symbolically represent him stand out: the peony and the fan, emblems of scholarly distinction; the scepter, symbolizing in this case the achievement of the literati’s ideals; the blossoming prunus, representing the beauty of virtue, and the peacock feathers that characterize high-ranking officials such as the literati.

In this suspended nature, the scholar’s face is portrayed with the realism of a living person. His baldness and the goatee emphasize the intent glance with which he looks at observers of this picture. If he was a Buddhist monk we could believe this to be a portrait of an enlightened man, but in the Confucian tradition it would be more appropriate to see him as a sage. But the two realities are by no means as different as they might seem.

No Comments