24 Jun TRIBAL DOORS of Central India

by Renzo Freschi, 1983

A vast region of central India—the states of Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand and Orissa—is still home to numerous tribes descending from the aborigines who since the Aryan invasions have slowly but surely been pushed into inaccessible and remote areas where they continued to live following their own traditions. Some of these tribes still use bows and arrows and live on hunting, fishing and on what they gather in the forest. Others practice a primitive form of agriculture, speak unwritten languages and orally hand down myths and traditions that distinguish them from those of the much larger Hindu population.

Verrier Elwin, the most important ethnologist who dedicated his life to studying and defending the adivasi (as tribal people are called in India), visited these regions from 1931 to 1945 and lived for long spells with their many ethnic groups. His The Tribal Art of Middle India (1951) is the only book specifically dealing with adivasi art, material culture and symbolic lore; Elwin’s books documented a variety of cultures which the Indians themselves consider savage.

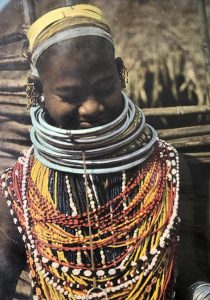

Some of the tribes in this vast area, such as the Kond and the Bondo, live in small isolated villages, in huts made of vegetal fibers. Men only wear small cotton loincloths; women wear a huge quantity of brass and glass bead necklaces and tens of metal bracelets. These tribes survive on the products of a basic agriculture and on barter, and they work for the landowners. Other tribes such as the Muria, Gond, Baiga, Santal and Soara, influenced by Hindu penetration, have more complex customs and more stable relations with the Hindu communities.

door 1

The mud-covered walls of their huts are adorned with plain floral or animal motifs. In their villages wooden pillars stand with totemic or commemorative functions, and massive wooden doors protect the more important houses.

The solid wood doors of these villages, single or double-leaf, are made of hand-hewn boards three to six cm in thickness, held together by sturdy laths secured on the outside by big hand-forged nails.

door 6

The vertical and horizontal laths are ornamented with lozenges, zig-zags, or herringbone patterns and form square panels in which the door figures or decorations are carved.

door 4, detail

The doors turn on two pivots at the top and bottom or they may be provided with two iron hinges mounted on spigots on the door jamb. Almost invariably they feature a thick iron chain secured to a ring on the wall so that a safety lock can be fitted.

In some cases door leaves are made from a single thick wooden board in which the panels are carved; this technique requires hard work, but it gives the door more strength and more prestige as well.

door 8

The carved panels normally feature a single figure in low relief technique, but there may be several figures suggesting a scene or action. A multi-headed animal signifies a herd, three fish with a single head represent a shoal of fish, a method which can also be observed in traditional Indian painting. However, the different subjects on one door do not as a rule appear to be connected in a single narrative.

door 2, detail

The themes depicted are those of daily life—animals, work, hunting, women carrying water jugs on their heads, convivial or ritual scenes—images of a culture in close relationship with nature.

door 2, detail

door 5, detail

Sometimes the influence of Hindu religion makes itself felt and we see the more popular gods like Ganesh, the elephant-headed god, and Hanuman, the lord of monkeys. These are very ancient divinities which Hindu religion drew from an animistic mythology connected with the realm of nature to which the the adivasi too always belonged. The carving of large rosettes in the shape of floral symbols or solar icons—universals in art—is also common.

door 1, detail

These figures have a symbolic meaning—fertility for the fish, stability for the tortoise, courage for the tiger, the rosette signifying the life-giving sun—but not all symbols can be interpreted, for they may belong to the history of a specific family or tribe.

Some door motifs can also be seen in the art of other ethnic groups and even from faraway regions, for instance on houses of Himachal Pradesh or embroidered on fabrics from various tribal groups in Gujarat and Bengal. These stylistic and thematic analogies (animals, riders, flowers etc.) are part of the wealth of “Indian folk art”, the result of thousands of years of interaction among different races, traditions, cultures and religions of the Indian subcontinent.

These images are striking in their simplicity and almost two-dimensional stylization of the figures, but this naive aspect is charged with “primitive” power and imagination. The harmonious large figures of door No. 1 (see fig. door 1) look like scenes from a comic book narrating the hunt for the crowned monkey (the god Hanuman?) and then describing the animals of the jungle.

In door No. 4 the frames are ornamented with an accurate carving, whilst the figures seem sketchy and stand out against the background thanks to a simple profile.

But these plain shapes and the cohesion of style make the door unique in its kind. There are also unusual elements, like the two elephants mounted by the mahout (the driver-trainer) and the important personage on the sedan chair, the hunter with his bow above which three huge fishes can be seen, and the abundance of animals on the other panels. The presence of the elephant on most tribal doors of central India derives from the importance this animal had when bushmen (the adivasi), who had always been hunter-gatherers, settled as farmers. It was thanks to the elephants that many forests were cut down and turned into arable land. Thus the elephant became a myth and finally, with the transformation of society and religion, a divinity.

door 4

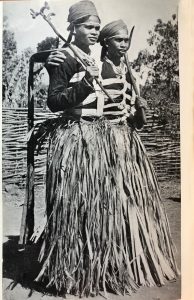

Door No. 2 is quite different with its vivid depiction of tribal life. The figures are well proportioned and realistically carved: the women’s straw skirts, the men’s pleated costumes, the jewels, the successful hunt, the convivial celebrations, the large birds’ feathers and the fishes’ scales give us a lively and elegant, almost idyllic picture of the community.

door 2, detail

The differences in style (at least three different styles can be observed in the published images) are due to cultural differences between the various ethnic groups, but also to their isolation, or conversely to their proximity to a developed society like that of India. For instance, the formal difference and aesthetic quality of door No. 2 almost certainly derives from the influence of classical Indian art. A comparison of Nos. 1, 4 and 6 with No. 2 (see photo at the end of the article) reveals two different worlds and modes of expression—the former three show a good process of synthesis while the latter elaborates a story, such as the transition from word to lexicon. Further elements of differentiation are the carver’s hand and the imagination he puts into his work.

door 7, detail

The doors of the Kuttia-Kond from Orissa have highly stylized figures, incised rather than carved. Baiga doors (Madhya Pradesh), the most plentiful, depict equally simple scenes, but with a higher relief of the carving, their aesthetics being simple and naturalistic, with pleasantly spontaneous essential lines.

door 6, detail

Doors from the Bastar area and from the Gond, Muria, Maria and Santal tribes are characterized by a more developed and refined taste. Each panel can contain even two or three subjects, as if to represent a more articulated story; aesthetic research is more evident in the more pronounced roundness of the figures, well proportioned and painstakingly finished.

door 2, detail

Geographic provenance of these doors is based upon examples and information from the already mentioned book by Elwin. Dating is uncertain. The doors published by Elwin were photographed in the 1930s and 40s and show clear signs of wear and tear. Some of those published here are no doubt older; others are more recent, but in no case later than the 1950s.

June 2013

Since 1983, when I wrote the first draft of this article for Archetipo—the mythical magazine by Vittorio Carini on primitive arts—almost everything has changed for India’s ethnic minorities (they constituted 8.3% of the population in 2011) and their art.

Following the country’s independence (1947) these age-old cultures have been faced with a process of modernization of society which has modified and often wiped out customs and traditions. In fact British administration during the Raj (as the colonial government of India was called from 1858 to 1947) was often brutal with the adivasi. Furthermore, the recent economic growth of the country, accompanied by an at times violent Hindu chauvinism, has changed tribal cultures and reduced their numbers, forcing them in some cases to leave their land and move to areas unsuited to their lifestyle. Some groups even isolated themselves in the forest in order to defend an identity they did not want to lose.

The disappearance of races and laguages, almost invariably due to violent causes, is part and parcel of the history of man, but being aware of that does not alleviate the pain.

After Verrier Elwin’s research and his struggle to protect Indian tribal culture in accordance with Gandhi’s philosophy of defending all minorities, these neglected people disappeared from the scene for decades.

Nevertheless, a few anthropologists and scholars have been active in the preservation of these traditions, and in fact in some Indian museums one can find sections dedicated to aboriginal races (which, however, are not recognized by the Indian constitution).

As a consequence, ethnic art too underwent transformation: costumes, fabrics, embroideries, furniture and anything belonging to material art manufactured as part of a tradition have turned into products for commercial sale, for furnishings, and for the tourist market, becoming an important means of survival for the minorities manufacturing them. The economy swept away or at least modified ancient customs but this too is part of the constant change in human society. As early as the 1940s Elwin, writing about adivasi material culture, stated that “The heyday of tribal groups has passed”. It is also for this reason that the doors in this article do not just have an aesthetic or cultural value, but they they are evidences of a lost tradition of which only artisan copies, quite different from the originals, are manufactured. They are in any case examples of the extraordinary creativity of all Indian ethnic groups.

Exhibits

- BAIGA TRIBE (?)

Central India, Madhya Pradesh

Single-leaf door with hinges, wood with dark patina

Cm 116 by 77

Where is the monkey-king (Hanuman?) running to, with his crown on the head while chasing his prey with a drawn bow and then continuing his race with a drawn sword and the tail looking like a liane, finally stopping by a tree? The gazelles (two, not one) are browsing, the elephant, king of the forest, steps onto a platform while the nosy peacock sticks its beak into a vase. Mythology and nature merge in these scenes of vibrant simplicity.

GOND TRIBE (?)

Central India, Madhya Pradesh

Single-leaf door made of nailed wooden boards and laths

Cm 150 by 82

Daily life in the village: two women lift their glasses to celebrate the hunters’ success; three more come back from the water spring carrying jugs full of water; the tiger—his male attributes quite evident—springs upon the prey; long-necked birds swallow fish like cormorants. Everything is described with pictorial precision—the women’s straw skirts, the men’s pleated costumes, the weapons, jewels (nose-rings, crowns and sumptuous collars), the large birds’ feathers, the fish scales, and the ever-present rosette opening as a lotus flower give us a realistic, but equally idyllic picture of the community. There is harsh reality here, but poetry as well. These details bear witness to the shift from a spontaneous and basic depiction of reality, as on most tribal doors, to an articulated and elegant aesthetic language, as on this one.

-

GOND TRIBE

Central India, Madhya Pradesh

Wood, wrought iron studs and hinges

Cm 157 by 81

This single-leaf door, made of boards held by round iron studs and braces, is unlike any other. There is one single human motif: two men wearing a simple loincloth, armed with clubs and with a shaven hair which might indicate hunters. One of them seems to carry a floral offer—could this be a ritual visit? All around is a kaleidoscope of various, very accurate geometric patterns; only the lower panels share the same rosette motif.

-

BAIGA TRIBE

Central India, Chhattisghar, Bilaspur district

Two-leaf solid wood door, wrought iron chain

Cm 176 by 87

The frames are decorated with an accurate carving, whilst the figures seem sketchy and stand out against the background thanks to a simple profile.

But these plain shapes and the unity of style make the door unique in its kind. There are also some unusual elements, like the two elephants mounted by the mahout (the driver-trainer) and the personage on the sedan chair, the hunter with his bow above which three huge fishes can be seen, and the abundance of animals which also include a dromedary, a scorpion and a peacock. All figures are armed, including the three at top right and the rider at bottom left. The association of armed men-hunters-elephants might indicate that this was the door of an important house, possibly that of the village chief.

-

BAIGA TRIBE

Central India, Chhattisghar

Two-leaf door, solid wood, wrought iron hinges and chain

Cm 152 by 90

Gods, men, animals and various geometric motifs are scattered on this door casually, as if the craftsman had followed his own creative inspiration seized by a sort of horror vacui. Ganesh—his large elephant head sitting on a thin human body—is flanked by a four-armed divinity in a yoga posture, her long neck wearing rings as do women of the Bondo tribe in this same area. A peacock sits on a perch at Ganesh’s feet as if it were not part of the scene and two parrots are beside the embracing couple in the lower panel. On the bottom more figures stand out against a thickly hatched background. The images are carved in depth and acquire unusual volume, like a true sculpture. The uncertain, quite naive ability of the artist is compensated by an impetuous and almost dramatic force.

-

BAIGA TRIBE

Centrale India, Madhya Pradesh

Two-leaf door, solid wood, wrought iron hinges and chain

Cm 147 by 78

This door describes a big popular event with three dancers moving in unison. The spectators watch some tribal cowboys ride standing up on not exactly quiet horses, as in a circus. On one panel we see the animals normally to be found in villages. For some mysterious reason the scene on one panel is shown vertically, so that the sensation of an exciting event packed with action is involuntarily enhanced. On the central lath are carved the long coils of a cobra, a sort of apotropaic presence meant to stop a real snake getting into the hut!

-

KUTTIA-KOND TRIBE (?)

Central India, Orissa

Single-leaf door made of five boards, iron studs and braces

Cm 147 by 80

An elaborate triple frame of tiny zig-zags encloses four elephants, plus a cat and a goat, and an isolated dog on the left. At bottom the curious figures of two women and a monkey are intent on a ritual dance. The monkey stretches with absolute elegance as if about to take a big leap. The scene is full of a wild, almost ecstatic dynamism reminiscent of a prehistoric graffito.

-

UNKNOWN TRIBE

Central India

Single-leaf door, wrought iron studs and hinges

Cm 157 by 81

The most elaborately decorated door in the collection is divided into 15 panels, each with a different subject. All animals of the forest can be seen—deer and gazelles, geese and peacocks, elephants and horses, and even a tiger. Two men at center seem to be contemplating this natural abundance. The floral motifs on the borders and chief of all the rosettes in each corner are quite similar to those

Credits:

Photo 1, 3: Bondo Girl da Bondo Highlander, V. Elwin, Oxford University Press, 1950

Photo 2: da L’Inde Inexplorée, V. De Golish, Ed. Arthaud, 1953

Photos: Pietro Notarianni

No Comments